Tuberculosis (TB): Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology

“The Plague Year - The New Yorker” plus 1 more |

| The Plague Year - The New Yorker Posted: 28 Dec 2020 03:01 AM PST  Operation Warp Speed, the government initiative to accelerate vaccine development, may prove to be the Administration's most notable success in the pandemic. Moderna's vaccine secured approval next. Its formulation proved to be 94.1 per cent effective in preventing infection and, so far, it has been a hundred per cent effective in preventing serious disease. Graham is happy that he chose to work with Moderna. In 2016, his lab developed a vaccine for Zika, a new virus that caused birth defects. His department did everything itself: "We developed the construct, we made the DNA, we did Phase I clinical trials, and then we developed the regulatory apparatus to take it into Central and South America and the Caribbean, to test it for efficacy." The effort nearly broke the staff. Moderna was an ideal partner for the COVID project, Graham told me. Its messenger-RNA vector was far more potent than the DNA vaccine that Graham's lab had been using. In another major development, Eli Lilly recently received an Emergency Use Authorization for a monoclonal antibody that is also based on the spike protein that Graham and McLellan designed. It is similar to the treatment that President Trump received when he contracted COVID. Graham had been in his home office, in Rockville, Maryland, when he got a call telling him that the Pfizer vaccine was breathtakingly effective—far better than could have been hoped for. "It was just hard to imagine," he told me. He walked into the kitchen to share the news with his wife. Their son and grandchildren were visiting. "I told Cynthia, 'It's working.' I could barely get the words out. Then I just had to go back into my study, because I had this major relief. All that had been built up over those ten months just came out." He sat at his desk and wept. His family gathered around him. He hadn't cried that hard since his father died. Graham and his colleagues will not become rich from their creation: intellectual-property royalties will go to the federal government. Yet he feels amply rewarded. "Almost every aspect of my life has come together in this outbreak," he told me. "The work on enhanced disease, the work on RSV structure, the work on coronavirus and pandemic preparedness, along with all the things I learned and experienced about racial issues in this country. It feels like some kind of destiny." More than a thousand health-care workers have died while taking care of COVID patients. Nurses are the most likely to perish, as they spend the most time with patients. On June 29th, Bellevue held a ceremony to memorialize lost comrades. Staff members gathered in a garden facing First Avenue to plant seven cherry trees in their honor. As the coronavirus withdrew from Bellevue, it left perplexity behind. Why did death rates decline? Had face masks diminished the viral loads transmitted to infected people? Nate Link thinks that therapeutic treatments such as remdesivir have been helpful. Remdesivir cuts mortality by seventy per cent in patients on low levels of oxygen, though it has no impact on people on ventilators. Amit Uppal told me that the hospital has improved at managing COVID. "We now understand the potential courses of the disease," he said. Doctors have become more skilled at assessing who requires a ventilator, who might be stabilized with oxygen, who needs blood-thinning medication. Then again, the main factor behind superior outcomes may be that patients now tend to be younger. When a patient is discharged, the event offers a rare moment for the staff to celebrate. On August 4th, a beaming Chris Rogan, twenty-nine years old, was wheeled by his wife, Crystal, through a gantlet of cheering health-care workers, in scrubs and masks. There were balloons and bouquets. After so much death, a miracle had occurred. Rogan was an account manager for a health-insurance firm in midtown. Crystal was a teaching assistant. In late March, he developed a low-grade fever and stomach discomfort, but he wasn't coughing. His doctor said that he probably had the flu. Rogan grew increasingly lethargic. He developed pneumonia. An ambulance took him to Metropolitan Hospital, on the Upper East Side. He still felt O.K., even when his oxygen level fell to sixty-four per cent. An hour after he checked in, he couldn't breathe. He was placed in a medically induced coma and intubated for nine days. During that time, the ventilator clogged and Rogan's heart stopped for three minutes. When he was brought back to consciousness, a doctor asked, "Did you see anything while you were dead?" "No," Rogan said. "I don't even remember being resuscitated." He began experiencing what hospital staffers told him was I.C.U. psychosis. He told Crystal that he'd been stabbed as a child. He began conversing with God. Just before he was intubated again, on April 15th, he felt certain that he would die in the hospital. He didn't wake up for sixty-one days. During that time, he was transferred to Bellevue, which was better equipped to handle him. It's a mistake to think that a patient in a coma is totally unaware. Rogan swam in and out of near-consciousness. When his doctor came in, he tried to talk to him: "Why am I awake? Why can't I move?" He couldn't sleep, because his eyes were partly open. "It's like being buried alive," he told me. His tenth wedding anniversary passed. Sometimes he heard Crystal's voice on video chat. "I hear you," he'd say, but she couldn't hear him. "I feel the tube down my throat, tell them to take me off the vent." A machine kept pumping oxygen into his lungs: psht! psht! psht! The sound pounded in his head. He would dream that he had left the hospital, then wake to find himself still there, the ventilator pumping away. "It was fucking torture," he said. He developed internal bleeding. Clots formed in his legs. He told God that he didn't want to die—that he had too much left to do. God assured him that he was going to make it. Crystal was charged with making choices for Rogan's care. The hardest one was the decision to amputate his right leg. It took three days to get him stable enough to perform the operation, which had to be done at his bedside, because he was too fragile to move. The doctors performed a guillotine amputation, just below the knee. Eight days later, they had to take off the knee. Rogan doesn't remember any of that. Some days, he is elated to be alive; other times, he asks himself, "What kind of quality of life is this?" Whether or not it was I.C.U. psychosis, he's clung to the experience of talking with God. When he emerged from the coma, he couldn't move his arms, but now his right hand is functional. After several weeks of rehab, he can walk a bit with a prosthetic leg. When he fell ill, there were only a hundred and fifty thousand cases in the U.S. When he left the hospital, there were more than four million. The death toll kept mounting, surpassing three hundred thousand at year's end. Some victims were famous. The playwright Terrence McNally was one of the first. The virus also killed Charley Pride, the first Black singer in the Country Music Hall of Fame, and Tom Seaver, one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history. Eighty per cent of fatalities have been in people aged sixty-five or older, and most victims are male. It's been strange to find myself in the vulnerable population. I'm a year younger than Trump, so his adventure with COVID was of considerable interest to me. If I get ill, I'm not likely to receive the kind of treatment the President did, but I'm in better physical condition, despite a bout of cancer. My wife, though, has compromised lungs. Even before the coronavirus put a target on our age group, mortality was much on my mind. Sometimes I'm dumbstruck by how long I've lived; when I'm filling out a form on the Internet, and I come to a drop-down menu for year of birth, the years fly by, past the loss of parents and friends, past wars and assassinations, past Presidential Administrations. On September 9th, our grandchild Gioia was born. She is the dearest creature. We stare into each other's eyes in wonder. Even in this intimate moment, though, the menace of contagion is present: we are more likely to infect the people we love than anyone else. Deborah Birx has recalled that, in 1918, her grandmother, aged eleven, brought the flu home from school to her mother, who died of it. "I can tell you, my grandmother lived with that for eighty-eight years," she said. Even before the election, Matt and Yen Pottinger had decided that they were tired of Washington. He was burned out on the task force, which had drifted into irrelevance as the Administration embraced magical thinking. They drove west, looking for a new place to live, and settled on a ski town in Utah. Matt will join Yen there once he wraps up his job in Washington. Pottinger's White House experience has made him acutely aware of what he calls "the fading art of leadership." It's not a failure of one party or another; it's more of a generational decline of good judgment. "The élites think it's all about expertise," he said. It's important to have experts, but they aren't always right: they can be "hampered by their own orthodoxies, their own egos, their own narrow approach to the world." Pottinger went on, "You need broad-minded leaders who know how to hold people accountable, who know how to delegate, who know a good chain of command, and know how to make hard judgments." At the end of October, before returning to D.C., Pottinger went on a trail ride in the Wasatch Range. As it happened, Birx was in Salt Lake City. Utah had just hit a record number of new cases. On the ride, an alarm sounded on Pottinger's cell phone in the saddlebag. It was an alert: "Almost every single county is a high transmission area. Hospitals are nearly overwhelmed. By public health order, masks are required in high transmission areas." Pottinger said to himself, "Debi must have met with the governor." Covid has been hard on Little Africa. "Some of our church members have passed, and quite a few of our friends," Mary Hilton, Ebony's mother, told me recently. "We just buried one yesterday. They're dropping everywhere. It's so scary." A cousin is in the hospital. "One out of eight hundred Black Americans who were alive in January is now dead," Hilton told me. "There would be another twenty thousand alive if they died at the same rate as Caucasians." She added, "If I can just get my immediate family through this year alive, we will have succeeded." She and two colleagues have written a letter to the Congressional Black Caucus proposing the creation of a federal Department of Equity, to address the practices that have led to such disparate health outcomes. Infected people keep showing up at U.Va.'s hospital at a dismaying pace. Hilton recently attended the hospital's first lung transplant for a COVID patient. He survived. Lately, more young people, including children, have populated the COVID wards. Hospitals and clinics all over the country have been struggling financially, and many health-care workers, including Hilton, have taken pay cuts. Thanksgiving in Little Africa is usually a giant family reunion. Everyone comes home. There's one street where practically every house belongs to someone in Hilton's family; people eat turkey in one house and dessert in another. Hilton hasn't seen her family for ten months. She spent Thanksgiving alone in Charlottesville, with her dogs. Thanksgiving was Deborah Birx's first day off in months. She and her husband have a house in Washington, D.C., and her daughter's family lives in nearby Potomac, Maryland. During the pandemic, they have been a pod. Recently, Birx bought another house, in Delaware, and after Thanksgiving she, her husband, and her daughter's family spent the weekend there. Her access to the President had been cut off since the summer, and, with that, her ability to influence policy. She had become a lightning rod for the Administration's policies. Then, in December, a news report revealed that she had travelled over the Thanksgiving weekend, counter to the C.D.C.'s recommendation. She was plunged into a cold bath of Schadenfreude. Old photographs resurfaced online, making it look as if she were currently attending Christmas parties. Birx indicated that she might soon leave government service. 20. SurrenderAustin bills itself as the "Live Music Capital of the World," but the bars and dance halls are largely closed. Threadgill's, the roadhouse where Janis Joplin got her start, is being torn down. The clubs on Sixth Street, Austin's answer to Bourbon Street, haven't been open for months. A band I play in has performed in many of them, but for the past several years we had a regular gig at the Skylark Lounge, a shack tucked behind an auto-body shop. Johnny LaTouf runs the place with his ex-wife, Mary. It's been shut since March 15th. "All small businesses have been affected, but music venues around the country were already in a struggle," Johnny told me. He's had to let go his ten employees—including three family members. That's only part of the damage. "When the musicians get laid off and the bands disperse and go their separate ways, then you've actually broken up their business." He added, "COVID killed off more than people with preëxisting conditions. Lots of businesses have preëxisting conditions." Lavelle White, born in 1929, was still singing the blues at Skylark until the doors closed. "Some of our greater musicians are older, because it takes a lifetime to master the craft," Johnny said. Skylark was a mixing bowl where younger musicians learned from their elders. "Now that pathway is broken." When Congress passed the CARES Act, which included money to support small businesses, local bars were not a priority. "There's no money," Johnny said Wells Fargo told him. He helps several older musicians with groceries, but he doesn't know how many in that crowd will ever return. Some have died from COVID. Two qualities determine success or failure in dealing with the COVID contagion. One is experience. Some places that had been seared by past diseases applied those lessons to the current pandemic. Vietnam, Taiwan, and Hong Kong had been touched by sars. Saudi Arabia has done better than many countries, perhaps because of its history with mers (and the fact that many women routinely wear facial coverings). Africa has a surprisingly low infection rate. The continent's younger demographic has helped, but it is also likely that South Africa's experience with H.I.V./AIDS, and the struggle of other African countries with Ebola, have schooled the continent in the mortal danger of ignoring medical advice. The other quality is leadership. Nations and states that have done relatively well during this crisis have been led by strong, compassionate, decisive leaders who speak candidly with their constituents. In Vermont, Governor Phil Scott, a Republican, closed the state early, and reopened cautiously, keeping the number of cases and the death toll low. "This should be the model for the country," Fauci told state leaders, in September. If the national fatality rate were the same as Vermont's, some two hundred and fifty thousand Americans would still be alive. Granted, Vermont has fewer than a million people, but so does South Dakota, which was topping a thousand cases a day in November. Scott ordered a statewide shutdown in March, which caused an immediate economic contraction. Governor Noem opposed mandates of any sort, betting that South Dakotans would act in their best interests while keeping the economy afloat. Vermont's economy has recovered, with an unemployment rate of 3.2 per cent—nearly the same as South Dakota's. But South Dakota has seen twelve times as many deaths. In Michigan, the state's chief medical officer, Joneigh Khaldun, is a Black emergency-room doctor. "She was one of the first to look at the demographics of COVID and highlight that we have a real racial disparity here," Governor Whitmer told me. "Fourteen per cent of our population is Black, as were forty per cent of the early deaths." The state launched an aggressive outreach to Black communities. By August, the rates of both cases and fatalities for Blacks were the same as—or lower than—those for whites. The vast differences in outcomes among the states underscore the absence of a national plan. The U.S. accounts for a fifth of the world's COVID deaths, despite having only four per cent of the population. In August, the Pew Research Center surveyed people from fourteen advanced countries to see how they viewed the world during the pandemic. Ninety-five per cent of Danish respondents said that their country had handled the crisis capably. In Australia, the figure was ninety-four per cent. The U.S. and the U.K. were the only countries where a majority believed otherwise. In Denmark, seventy-two per cent said that the country has become more unified since the contagion emerged. Eighteen per cent of Americans felt this way. |

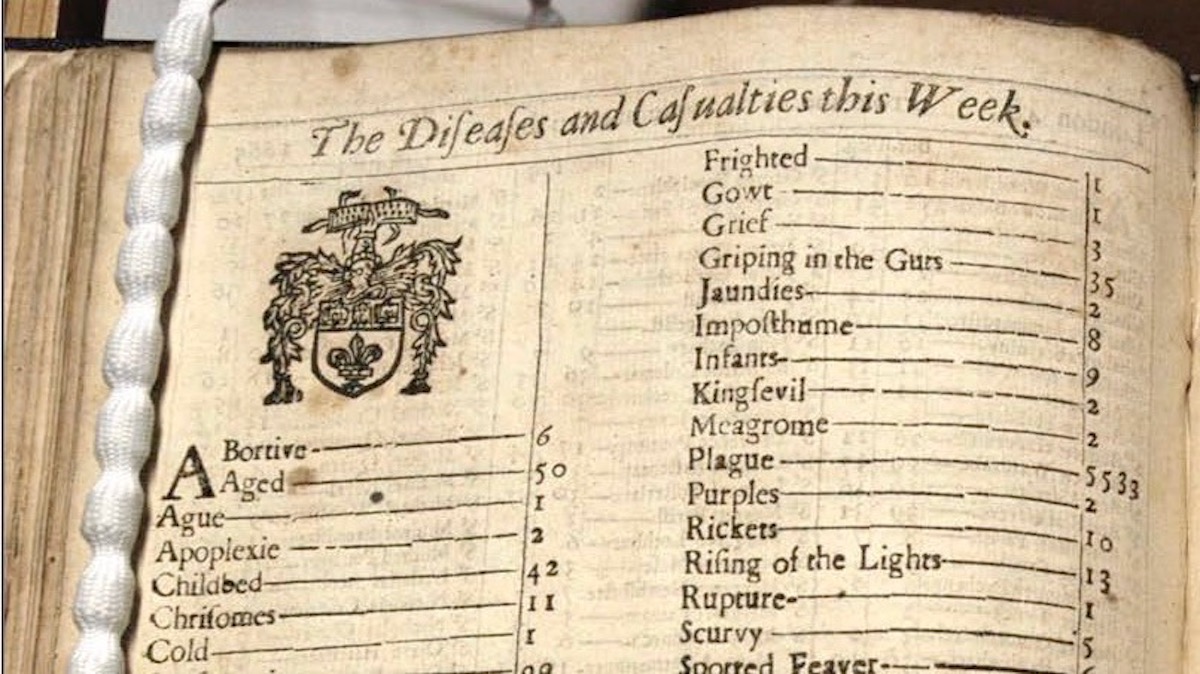

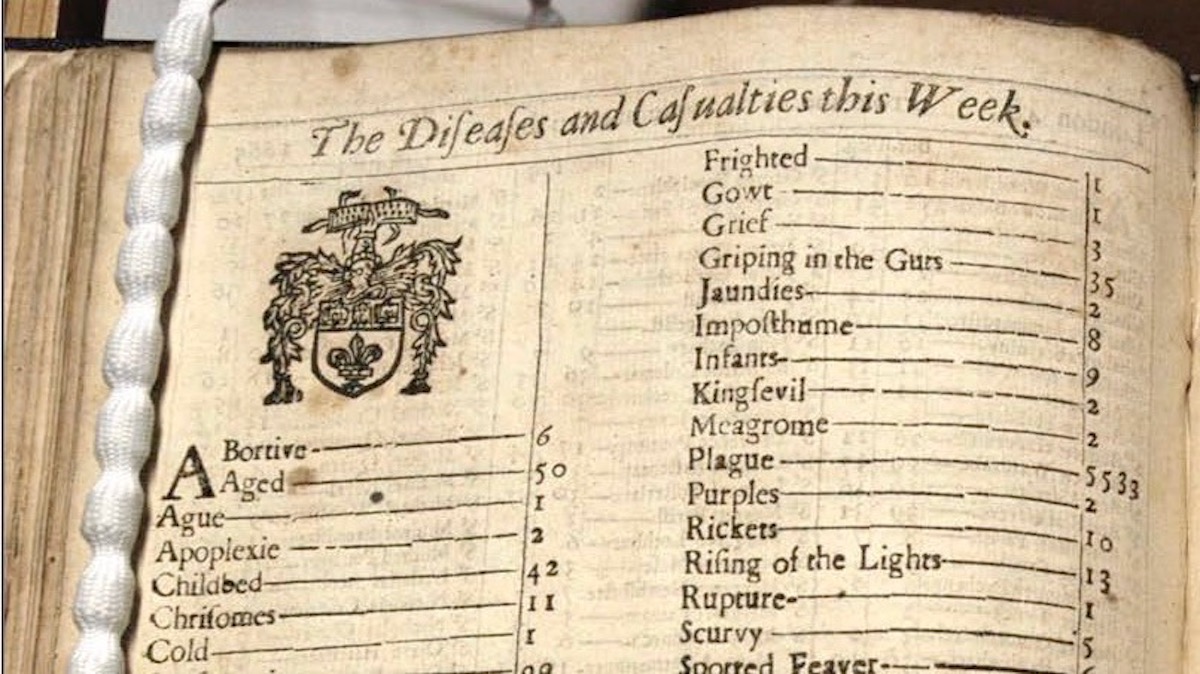

| Plague spread quickly in Medieval Europe - Cosmos Posted: 21 Oct 2020 12:00 AM PDT   One of the London Bills of Mortality for the week beginning 26 September 1665. Credit: Claire Lees The speed of plague transmission in London increased four-fold between the Black Death of 1348 and the Great Plague of 1665, according to a new study. In the 14th century the number of people infected during an outbreak doubled about every 43 days; 300 years later, it was every 11 days. The researchers believe population density, living conditions and cooler temperatures could potentially explain the acceleration, and that the transmission patterns of historical plague epidemics offer lessons for understanding modern pandemics. "It is an astounding difference in how fast plague epidemics grew," says David Earn from Canada's McMaster University, who led a team that included statisticians, biologists and evolutionary geneticists. As no published records of deaths are available for London prior to 1538, they estimated death rates by analysing historical, demographic and epidemiological data from three sources: personal wills and testaments, parish registers, and the London Bills of Mortality. "At that time, people typically wrote wills because they were dying or they feared they might die imminently, so we hypothesised that the dates of wills would be a good proxy for the spread of fear, and of death itself," he says. "For the 17th century, when both wills and mortality were recorded, we compared what we can infer from each source, and we found the same growth rates." While previous genetic studies have identified Yersinia pestis as the pathogen that causes plague, little has been known about how the disease was transmitted. "From genetic evidence, we have good reason to believe that the strains of bacterium responsible for plague changed very little over this time period, so this is a fascinating result," says Hendrik Poinar, a co-author of the team's paper in the journal PNAS. The estimated speed of these epidemics, along with other information about the biology of plague, suggest, the researchers say, that during these centuries the plague bacterium did not spread primarily through human-to-human contact, known as pneumonic transmission. Growth rates for both the early and late epidemics are more consistent with bubonic plague, which is transmitted by the bites of infected fleas.  CosmosCurated content from the editorial staff at Cosmos Magazine. Read science facts, not fiction...There's never been a more important time to explain the facts, cherish evidence-based knowledge and to showcase the latest scientific, technological and engineering breakthroughs. Cosmos is published by The Royal Institution of Australia, a charity dedicated to connecting people with the world of science. Financial contributions, however big or small, help us provide access to trusted science information at a time when the world needs it most. Please support us by making a donation or purchasing a subscription today. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "how is plague transmitted" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment