Tuberculosis (TB)

“China: 3-year-old diagnosed with Bubonic plague; is 'Black Death' back? All you need to know - DNA India” plus 3 more |

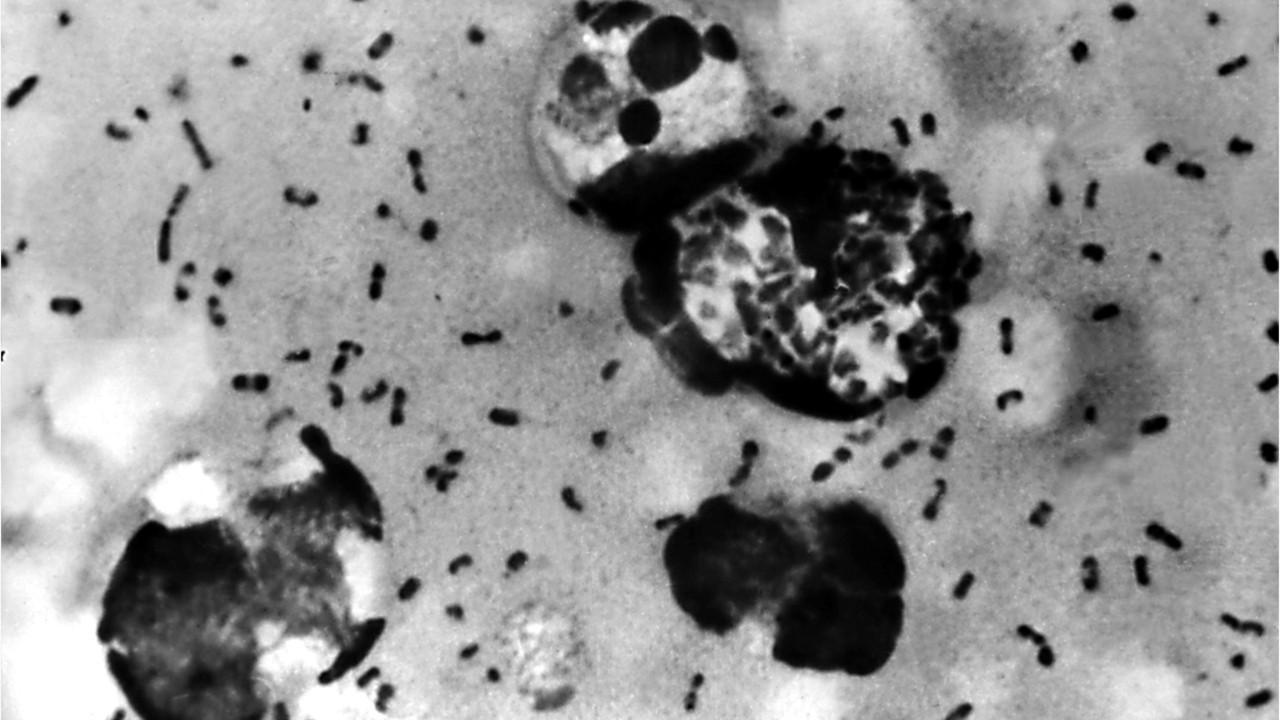

| Posted: 30 Sep 2020 03:17 AM PDT A boy in China has been infected with bubonic plague, a centuries-old disease that caused a major outbreak in 2009, Fox News reported. The 3-year-old from Menghai county, located in southwestern China, suffered a mild infection but is now in stable condition following treatment, the Global Times of India reported. No other infections have reportedly been identified. Chinese authorities in the region have started a level IV emergency response to prevent another epidemic following the Covid-19 outbreak, reported Global Times. The boy's case came to light following a countywide screening for the disease, which was prompted after "three rats were found dead for unknown reasons in a village," the outlet reported. Earlier, in August, authorities in North China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region had sealed off a village after a resident died of Bubonic plague. Inner Mongolia had also reported four cases of bubonic plague in November 2019. What is plague?Plague is an infectious disease, caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, a zoonotic bacteria usually found in small mammals and their fleas. People can contract plague if they are bitten by infected fleas, and can develop the bubonic form of plague. Sometimes bubonic plague progresses to pneumonic plague when the bacteria reach the lungs. Common antibiotics are efficient to cure plague, only if they are given at an early stage. Plague can be a very severe disease in people, with a case-fatality ratio of 30% to 60% for the bubonic type, and is always fatal for the pneumonic kind when left untreated. Is person-to-person transmission possible?Person-to-person transmission is possible through the inhalation of infected respiratory droplets of a person who has pneumonic plague. Types of plagueThere are two main forms of plague infection, depending on the route of infection. 1. Bubonic plague It is the most common form of plague globally and is caused by the bite of an infected flea. Human to human transmission of bubonic plague is rare, reports WHO. However, it can advance and spread to the lungs, which is the more severe type of plague called Pneumonic plague. 2. Pneumonic plague (lung-based plague) It is the most virulent form of plague. Incubation can be as short as 24 hours. Any person with pneumonic plague may transmit the disease via droplets to other humans. Untreated pneumonic plague can be fatal. However, recovery rates are high if detected and treated in time (within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms). Symptoms of bubonic plagueSymptoms include fever, chills, head and body aches and weakness, vomiting, and nausea. Painful and inflamed lymph nodes can also appear during the bubonic plague. Prevention and treatmentTo prevent bubonic plague, avoid touching dead animals, and wear insect repellent while in plague endemic areas. Plague can be treated with antibiotics, and recovery is common if treatment starts early. In plague-outbreak areas, people with symptoms should go to a health centre for evaluation and treatment. Currently, the three most endemic countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, and Peru. The plague that caused 50 million deaths in 14th centuryChina has largely eradicated the plague, but occasional cases still occur. The country has reported 26 cases and 11 deaths from 2009 to 2018. Historically, the plague was responsible for widespread pandemics with high mortality. It was known as the "Black Death" during the fourteenth century, causing more than 50 million deaths in Europe. |

| Bubonic plague infects boy, 3, in China: report - Fox News Posted: 29 Sep 2020 09:45 AM PDT  A 3-year-old boy in China has been infected with bubonic plague, according to a report. The child, from Menghai county, located in Yunnan Province in southwestern China, suffered a mild infection but is now in stable condition following treatment, the Global Times of India reported. No other infections have reportedly been identified. The boy's case came to light following a countywide screening for the disease, which was prompted after "three rats were found dead for unknown reasons in a village," the outlet reported. Known as the "Black Death," bubonic plague can be fatal in up to 90% of people infected if not treated, primarily with several types of antibiotics. An outbreak in the Middle Ages killed millions of people. COLORADO REPORTS FIRST HUMAN PLAGUE CASE SINCE 2015: OFFICIALS Pneumonic plague can develop from bubonic plague and results in a severe lung infection causing shortness of breath, headache and coughing. China has largely eradicated plague, but occasional cases are still reported. Inner Mongolia reported four cases of bubonic plague in November 2019, according to Bloomberg, while Mongolia, a country that borders the Chinese autonomous region, reported two cases earlier this year. "Infected rats are a key source of the disease, which also transmits to humans through bites from infected fleas," Wang Peiyu, a deputy head of Peking University's School of Public Health, told Global Times. He claimed the disease is "unlikely to spread" in Yunnan. More specifically, the organism Yersinia pestis causes the disease. MONGOLIAN TEEN DIES OF BUBONIC PLAGUE AFTER EATING INFECTED MARMOT Symptoms of bubonic plague — the most common form of the disease, per the Mayo Clinic, and not to be confused with septicemic and pneumonic plague — include swollen lymph nodes commonly in the armpit, neck or groin, as well as fever, headache, fatigue and muscle aches. Fox News's Stephen Sorace and the Associated Press contributed to this report. |

| Epizootic: How Plague Took Hold in Western Wildlife - Bay Nature Posted: 27 Sep 2020 08:14 AM PDT

Plague's story in the U.S. begins 120 years ago, in the basement of the Globe Hotel, a cheap rooming house on Dupont Street in San Francisco's Chinatown. Wong Chut King, a 41-year-old lumberyard worker who had immigrated from China's Guangdong Province 16 years before, shared a windowless room beneath the hotel's sidewalk with three other immigrants. They took turns sleeping in the room's single bed. Water from an underground cesspool seeped through the walls. An open sewage pipe ran above the room. At the end of February 1900, King came home with a lump in his groin that quickly became so painful he could not urinate or move. As his temperature climbed, his tongue turned white and furry and sores sprouted across his lips. For days he was racked with vomiting and diarrhea. When he fell into a coma, his roommates, skeptical about his survival, took him to a nearby coffin shop. King died there March 6. The lump in his groin was a telltale sign. When city bacteriologist William Kellogg showed up to inspect King's body, he immediately suspected the plague. The city's Board of Health quickly cordoned off Chinatown, surrounding it with blockades guarded by police. The San Francisco Chronicle called Kellogg's diagnosis a "bubonic bluff"—plague had never occurred in the U.S. But Kellogg knew that the ancient disease had recently cropped up in ports across the Pacific. Only months before, it had caused such a severe epidemic in Honolulu that desperate health officials there had burned down patients' homes to stop its spread. Chinatown residents feared the same would happen in San Francisco, especially as the police allowed whites to cross the cordon while they prevented Chinese residents from leaving. Chinatown was home to 30,000 people confined to a 12-block radius by racist redlining practices that denied Chinese immigrants access to other parts of the city. In its crowded, brick-and-wood tenements, rooms for one or two housed eight, running water was scarce, and indoor plumbing was either nonexistent or "grossly inadequate," says Susan Craddock, a professor of gender, women's, and sexuality studies at University of Minnesota and author of City of Plagues. A group of prominent Chinatown business leaders, convinced the quarantine was a pretext for discrimination, hired lawyers and threatened to sue the city. When no new plague cases appeared after three days, the city relented and the cordon came down. But the act proved hasty. Dead rats began to appear in Chinatown's courtyards and alleyways. And then word came back from a quarantine officer of the federal Marine Hospital Service, Joseph Kinyoun, who had tested samples from King in his lab on Angel Island. Kinyoun confirmed Kellogg's diagnosis: King had in fact died of plague. And as March turned to April, several more Chinatown residents succumbed to the disease. Chinatown leaders denied the reports of plague—and, fearful of an epidemic's economic repercussions, so did others in power. Mayor James D. Phelan sent telegrams to the mayors of dozens of other cities, assuring them that San Francisco had seen just a single, isolated case—nothing more. Governor Henry Gage told reporters that Kinyoun had caused San Francisco's cases himself, by letting the plague germ escape his lab. Gage even proposed making it a felony for newspapers to publish "false" reports on the presence of plague in the state. They all had good reason for the denials. Kinyoun was urging for a naval quarantine to keep ships from entering or leaving the city's ports, as well as mandatory health passes for any San Franciscans who wanted to leave the city by sea or land. Neighboring states threatened to block travelers and goods coming out of California. Admitting to plague would devastate tourism and trade, wrote Marilyn Chase in Barbary Plague: The Black Death in Victorian San Francisco. "No one wanted to see the yellow flag of pestilence flying over the portal to the Golden Gate." An Ancient DiseasePlague's centuries-old reputation preceded its arrival in the City by the Bay. In the sixth century, the Plague of Justinian ravaged Europe, Asia, and Africa, claiming nearly a hundred million lives before it burned itself out. A second pandemic began in the fourteenth century, originating in Asia and spreading along trade routes to Europe, where it quickly killed a quarter of the population and became known as the Black Death. In the 1850s, a third pandemic began with a series of small outbreaks in southern China. By the 1890s, those outbreaks had spread to commercial coastal cities, killing over 2,500 people in Hong Kong and 35,000 people in Canton. All the while, ships arrived and departed from those cities' ports, taking the disease with them. In 1899, one such ship docked in Honolulu, triggering an outbreak there. In the midst of one outbreak, the steamship Australia stopped at the Honolulu port before departing for San Francisco. When the SS Australia arrived in San Francisco, it delivered rats along with its passengers and cargo, and the rats scurried into sewer pipes that ran from the city's port a mile up to Chinatown. "At that time, ships had a lot of rats on them, and it's not really too surprising at all that plague was in some of those rats," says Dean E. Biggins, a U.S. Geological Survey wildlife biologist who studies plague's ecology. Brown rats (Rattus norvegicus), native to China, are important in spreading the plague, but they don't act alone. The rodents are one of many mammals that can host the rod-shaped plague bacterium, the Yersinia pestis bacillus, in their bodies. Fleas transmit the bacillus from rodents to other mammals. When a rat flea, such as Xenopsylla cheopis, bites an infected rat to feed on its blood, the bacillus subsequently multiplies so copiously inside the flea's digestive system that clumps of bacteria soon block its gut. When the hungry flea tries to feed off of a new host, it regurgitates the bacteria into the bite wound. Plague experts now know that at least thirty different flea species can transmit plague, and that some of them are better at it than others. The domestic rat flea Nosopsyllus fasciatus can spread plague, as can the mouse flea Malaraeus telchinum and the ground squirrel flea Oropsylla montana—formerly Ceratophyllus acutus—is now the most important flea vector of plague in the U.S. In San Francisco in 1900, the flea vector that did most of the work, according to medical historian Guenter Risse, author of Plague, Fear, and Politics in San Francisco's Chinatown, was the rat flea Nosopsyllus fasciatus. Fleas that take a plague-infested blood meal often die of hunger and dehydration. In rats, the plague bacillus quickly wreaks havoc. The rodents can develop painful and debilitating buboes from the infection, as the bacillus destroys their organs and spreads to their lungs. And then, within a few days, "they just drop dead," says Paul Mead, chief of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Bacterial Diseases Branch in Fort Collins, Colorado. When fleas have infected enough rats that the rat population begins to drop, the fleas seek other warm-blooded hosts to feed on. And when rats live in close quarters with people, as they did in San Francisco's Chinatown, those people are the most convenient hosts. Cycles of PlagueScientists recognize two cycles of plague, an urban cycle, in which flea bites transmit the disease from rats or other rodents to people, and a sylvatic cycle, in which fleas transmit the disease among susceptible hosts in the wild. But when plague arrived in San Francisco in 1900, it was an exclusively urban disease, in part because the cramped quarters of urban poverty created such ideal conditions for its spread. In people, the plague manifested in two forms: bubonic, in which bites from infected fleas cause the lymph nodes to swell into painful buboes, like the one in King's groin, and pneumonic, which develops when the infection spreads to the lungs or when a healthy person inhales the exhalations of the sick. (A third form, septicemic plague, develops when the bacillus multiplies in the bloodstream.) For the next three years, plague continued its spread through the city, from person to person, and from rat to flea to person. It moved quickly at first, then sporadically. Under the direction of Kinyoun, and then his successor Rupert Blue, an assistant surgeon with the Marine Hospital Service, the city's health department washed and fumigated thousands of residences to eliminate fleas. They tore down dilapidated balconies, platforms, and decks harboring rats in their nooks and crannies. By the time the extermination campaign was complete, San Francisco had suffered 121 cases, 113 of them fatal. That 93 percent mortality rate signaled plague's primarily pneumonic spread. "Plague is at its most lethal when it is transmitted from lungs to lungs," wrote Risse. The small number of cases, meanwhile, was due to the inefficiency of the local flea vector, its breeding compromised by a concurrent relative drought, as well as pneumonic plague's gruesome symptoms, which included violent and bloody coughing at its most contagious stage. Plague in that form, said Mead, "produces a lot of fear and a lot of social distancing without any sort of encouragement." Mayor Phelan was among the fearful; he never admitted to the disease's presence in his city. But in 1903 his successor, Eugene Schmitz, along with the new governor, physician George Pardee, signed a declaration of plague's existence in the state.

That same year, Blue received word of a patient at San Francisco's German Hospital. A blacksmith from Pacheco, a former port town near Suisun Bay, was in dire condition; his buboes indicated plague. Plague wasn't known to exist outside the city, so Blue crossed the Bay to investigate. He learned that the blacksmith had never traveled to San Francisco, or even Oakland. But days before he fell ill, he shot and collected several California ground squirrels (Otospermophilus beecheyi). The next month, San Francisco's Southern Pacific Hospital admitted a man in similar condition, from San Ramon; he, too, had the plague. Blue learned that the man had been working in a railroad camp where the laborers often killed and dressed ground squirrels for food. Blue dispatched a physician to travel across Alameda and Contra Costa counties inquiring about ground squirrels. The ranchers and farmers there reported that occasionally the rodents went missing from places where they had once been common. People didn't mind: on managed land, the burrowing rodents were considered pests. One rancher even said he had heard of other ranchers tracking down sick and dead ground squirrels and bringing them back to their own land, hoping to spread whatever the animals had. Blue sent a team of men to collect rodents in Contra Costa County for testing. Few of the more than 500 animals they caught were infected with plague. But Blue's successor, William Wherry, was skeptical of the finding. He spent the next few years documenting evidence of plague in East Bay ground squirrels himself.

|

| During pandemic, ‘Black Death’ scholar attracts doom-oriented fan base - Washington Post Posted: 04 Sep 2020 12:00 AM PDT  "That's the only time I felt famous," said Armstrong, an expert in medieval studies who heads the English department at Purdue in Indiana. "I got a really cool drinking horn. And whenever I teach 'Beowulf,' I bring it out and I pass it around." But since the start of the pandemic, Armstrong, 49, has gained a whole new level of acclaim for her Old World expertise. She's the narrator of "The Black Death: The World's Most Devastating Plague," a video series that became must-see TV this spring when it aired on Amazon Prime, just as stuck-at-home, 21st-century humans were reeling from the coronavirus crisis. In 24 surprisingly compelling episodes, Armstrong introduced the devastation of the mid-14th century to doom-obsessed modern viewers. The flea-driven plague, also known as the "Great Mortality," overran Eurasia and North Africa from 1347 to 1353, killing tens of millions of people and wiping out half of Europe's population. The series was filmed before the coronavirus pandemic, in 2016, as part of The Great Courses, a compendium of college-level audio and video lectures. But "The Black Death" has spurred a broad cult following for Armstrong — even as it underscores the dismaying parallels between the great plague and the deadly disease now circling the globe. "I just wish that the course were not quite so relevant at the moment," said Armstrong, whose parents and siblings are among those who have contracted covid-19 and recovered. Since March, she has received a stream of daily emails from people who binge-watched "The Black Death," all wanting to know whether things are as bad now as they were back then. The answer, thankfully, is no, Armstrong said. Although covid-19 has infected more than 26.3 million people and killed at least 869,500 worldwide, the proportion of deaths doesn't compare with the devastation caused by the "Great Mortality." The ferocious pandemic was dubbed the bubonic plague, reflecting the painful and (at the time) mysterious swellings, known as buboes, that developed in the lymph nodes of the neck, armpits and groin of those infected. The swellings oozed blood and pus, even as the unfortunate patients suffered other terrible symptoms: fever, chills, body aches, vomiting and diarrhea — often followed quickly by death. The disease could take other grisly forms, Armstrong said: pneumonic plague, which infects the lungs, and septicemic plague, where the infection spreads to the blood, often causing skin on the fingers, toes and nose to blacken and die. The Black Death originated in China and spread along trade routes, turning the Silk Road into a superhighway of infection. It arrived in many places via trading ships, long believed to be carried by the fleas on rats that coexisted closely with humans. A more recent theory contends that fleas and lice on humans themselves helped spread the disease widely. As deaths mounted, populations in region after region struggled vainly to understand its cause or cure. "The good news is that, all things considered, we are in a much better position than those poor people who had to survive the Black Death," Armstrong said. "The mortality rate for the Black Death, for those who contracted it, was something like 80 percent. And we're still in single digits." The modern world also has the advantage of seven centuries of scientific discovery that can root the current pandemic in a rogue coronavirus and target a treatment — and ultimately a cure — based on that understanding. By contrast, humans suffering through the Black Death blamed an unfavorable conjunction of planets, "bad air," earthquakes and God's wrath. It wasn't until 1894 that Swiss scientist Alexandre Yersin discovered the bacillus that caused the plague: Yersinia pestis, named in his honor. "During the Black Death, what was really terrifying about that is they really had no idea at all what it was," Armstrong said. "They had no good science to help them figure out how to cope with it." Still, there are some unsettling similarities between societal responses to the plague and covid-19. In both cases, some officials tried to downplay the severity of the outbreak and the far-reaching economic and social effects. In Florence, for instance, members of the elite ruling class, decimated by the plague, faced a rebellion from the newly powerful working class, Armstrong said. Many people, from ordinary peasants to local religious leaders, took the plague seriously and tried to carry out their normal duties. Clergy members were called to the homes of the ill to provide last rites, often contracting the disease in the process. Others, however, ignored the calamity, turning to hedonism and debauchery, "figuring that if they were going to die, they might as well enjoy themselves," Armstrong said. "What I would say is that people are the same then as now," Armstrong said. "Humans, when they're together in a large group, often do dumb things. And it's frustrating that so many people don't seem to be learning lessons from the past." It has been "particularly horrifying," Armstrong said, to see Asian Americans targeted as the presumed cause of the covid-19 crisis. During the plague, Jews were scapegoated — and killed — as the possible source of the scourge. "To think that anyone thinks you can call it 'kung flu,' which is so racist," Armstrong said, referring to President Trump's characterization of covid-19. "It's really distressing. We have international travel. Wherever it originated, it would have spread around the globe." Amazon Prime officials wouldn't say how many people have viewed the series since March. But Cale Pritchett, vice president of marketing for The Great Courses, said tens of thousands of viewers have watched the show each month for the past four years. "It has been a constant in our top 10," he said. "For a while, it was No. 1." Armstrong's clear mastery of the subject — her doctorate is in medieval literature — and her easygoing teaching style make for engaging television. The show is set in an office decorated with replicas of skulls, bones and a distinctive beaked doctor's mask that was filled with sweet-smelling flowers to ward off the plague. Prop rats migrate around the set. Armstrong, who favors brightly colored blazers, stands to talk through the 12 hours of lectures, striding back and forth across an ornate woven rug. She leavens the often-grisly subject matter with dark humor, reminding viewers, for instance, that the bodies of plague victims have been described as being layered in mass graves the way cheese is layered in lasagna. In the more than 300 reviews of the series online, viewers note her approachable style. "She doesn't come across as an intellectual snob," wrote one. "I wish I would have had her as a professor when I was in college." Because of her familiarity with the plague, Armstrong was alarmed this year when early reports emerged of an unknown virus spreading through China. "I'm always worried about pandemic," said Armstrong, the mother of 13-year-old twin daughters. "I have peanut butter and toilet paper and water in a cabinet in the basement, even when there is no threat of a pandemic, because that is the situation that is the scariest. Especially if it's a novel virus, which is what this is." In recent months, Armstrong's fears were realized as four family members — her parents in Seattle, her brother in New York and her sister in the San Francisco Bay area — contracted covid-19. They've all since recovered, although her mother was hospitalized and received the antiviral drug remdesivir to aid her healing. If there's one strong parallel between the Black Death and the current pandemic, it's the social upheaval spurred by both, Armstrong said. The 14th-century plague upended the rigid social structure of the era, which had confined people to narrow roles of clergy, nobility and peasant. "Humanity came back after that," Armstrong said. "And some people would argue that it was that external pressure that changed society so radically that gave us eventually things like the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation that all have their roots in that major event." Perhaps current protests and calls for political, economic and social change may have lasting impact, too. "My hope is that we get something good out of this," Armstrong said. — Kaiser Health News Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "pneumonic plague" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment