Lung microbiome: new insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases

“How fear and politics slowed response to the bubonic plague that hit SF in 1900 - San Francisco Chronicle” plus 2 more |

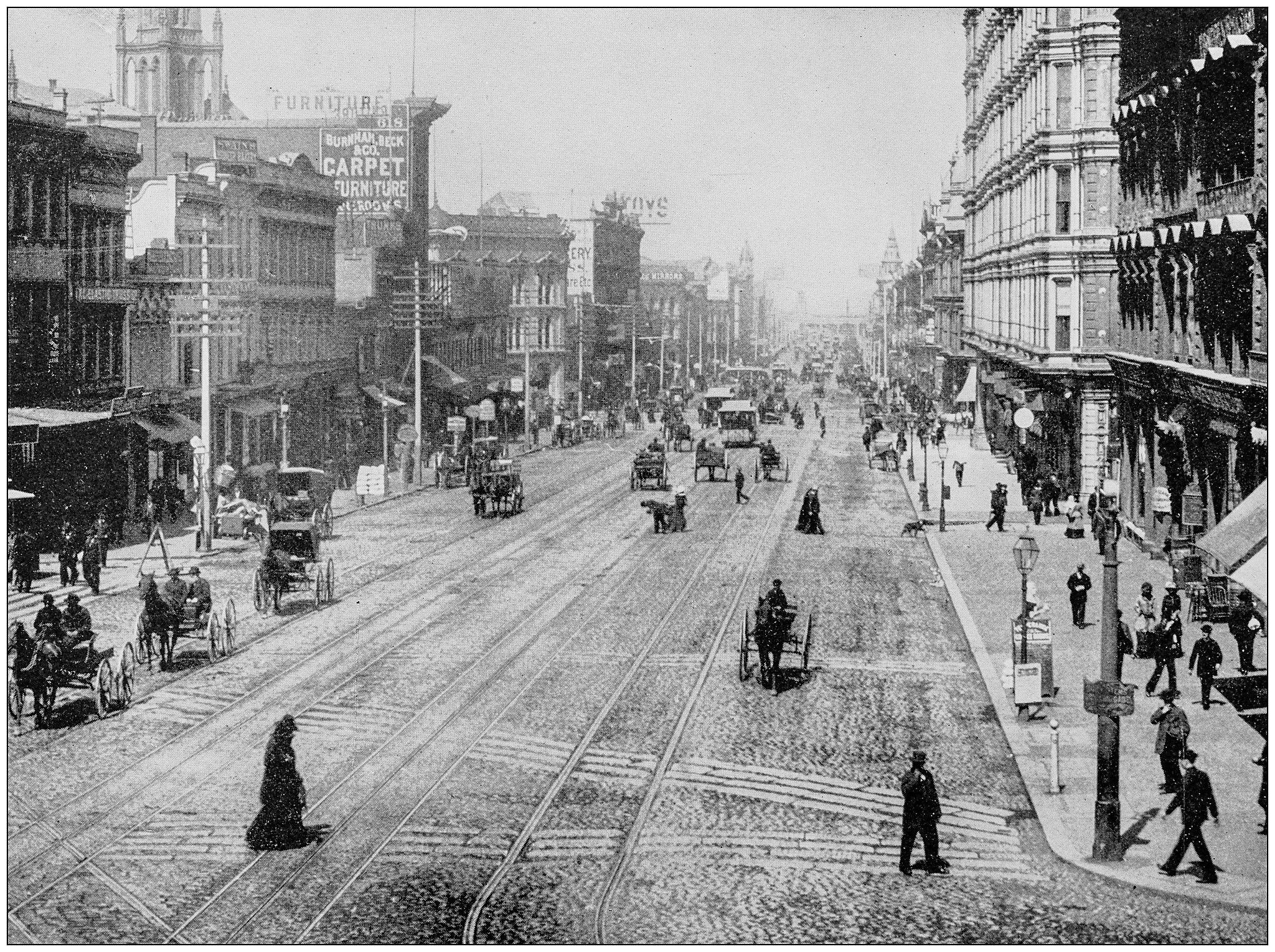

| Posted: 20 May 2020 04:26 AM PDT  Disease struck and politicians blamed the patients, their country of origin and the public health officials who delivered the diagnosis. It's an old story. Public health warnings were dismissed as a "scare," and a politically motivated "hoax." Thugs, fueled by fear and xenophobia, hurled slurs and attacks on Asian Americans. But blame-shifting and scapegoating of Chinese people just delayed care, and made the population less safe. Politicians sidelined public health experts who delivered stark truth or strayed from the party line. Meanwhile, the powerful and their sycophants prematurely declared that the foe was on the run and we were open for business. Even after the ranks of the sick grew to include people of every background, the racializing of disease still tainted our public discourse. This isn't just a snapshot of the coronavirus in 2020; it's also a picture of the bubonic plague that hit San Francisco in 1900. Back then, much like today, the knee-jerk reactions — deny, delay, divert and blame — made it harder for doctors and scientists to do their job of preventing cases, treating patients and eradicating the disease. As I wrote in my book "The Barbary Plague: the Black Death in Victorian San Francisco," political roadblocks to public health are common and costly. They're also as predictable as the movie "Groundhog Day." In 1900, scapegoating, cover-ups and faux conspiracy theories were the order of the day. One official even accused doctors of injecting corpses with plague germs to prove their diagnosis, and control the city's health bureaucracy. San Francisco could have quashed plague quickly by attacking the real threat — infected rat fleas — rather than blaming patients or demeaning doctors. In 2020, the U.S. could have pursued the coronavirus by nationalizing mask, gown and ventilator production, and adopting the World Health Organization's early coronavirus test in January — to access adequate supplies and an earlier picture of viral spread. We were late to these tasks because Washington wasted time, railing at the Chinese and imputing dark motives to the WHO. At home, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, long our premier source of epidemic intelligence, has grown quiet. Whoever muzzles the CDC imperils U.S. health. But while politicians and their cynical allies fiddle, plague burns. Back in 1900 San Francisco, a cover-up allowed plague to smolder underground, igniting a second wave after the 1906 earthquake. In the end, it took until 1910 to declare real victory. The delay exacted another permanent price. Delays in rodent eradication gave plague rats plenty of time to travel into the East Bay hills, and migrate further east to the Rocky Mountains. There the virus remains endemic today in squirrels and prairie dogs, infecting people each year in states like New Mexico. Studies show it's the same strain of the plague bacillus that affected San Francisco in 1900. The only difference is, today's patients have lifesaving antibiotics. Because there's no cure for coronavirus, promoting quack cures and delaying testing, tracking and tracing will all cost lives. The only sure thing — like death and taxes — is that we share the world with microbes. For decades, our best scientists cautioned us that we would see the rise new pandemic diseases. But the current administration disbanded the Office of Pandemic Preparedness, only to claim — incredibly — that no one saw this new scourge coming. Scientists saw it; Washington ignored it. The names of the diseases, their symptoms, speed of travel and style of transmission change. Sadly, human nature does not. Just like the 1918 "Spanish flu (which probably started in Kansas) and 15th century "French disease" (syphilis, which went everywhere) global pandemics trigger predictable rounds of buck-passing. Demonizing our neighbors around the world and subjecting science to political spin leaves only one victor standing: the virus. As for San Francisco? Our city has come a long way since the 1900-era dealmakers in City Hall and Sacramento cut a deal to cover up the plague. This year, Mayor London Breed and Gov. Gavin Newsom imposed a shelter-in-place program that flattened the rising curve of COVID-19 cases. Let's stay on course, and keep putting people before plague politics. Marilyn Chase is a journalist, author and instructor at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. Her latest book is "Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa" (Chronicle Books, April 2020). |

| Pandemics come and go. The way people respond to them barely changes. - The Washington Post Posted: 07 May 2020 08:25 AM PDT  I'm a historian who studies medicine in 17th century England, and lately I've been thinking about one particular pandemic: the bubonic plague that struck Britain in 1665, killing at least 200,000 people, including about 15 percent of the population of London. As we struggle to deal with the coronavirus pandemic, what strikes me most is how similar our experiences and responses are to those of the people living in England more than three centuries ago. No Zoom, no Instacart, no "Tiger King," but human behavior in the face of plague seems remarkably familiar. Just as today, a global economy was a key driver of the English epidemic. Bubonic plague, which is bacterial rather than viral, is typically spread to humans by fleas who have fed on the blood of infected rats. Earlier plague epidemics — such as the Black Death of the 1300s, which may have wiped out half the population of Europe — came to Europe via merchants traveling back from Asia along the Silk Road. In the same way, contemporary observers reported that the 1665 epidemic may have been brought to London by Dutch trading ships; the epidemic had already spread there a year earlier. In the months before it reached England, authorities had tried, obviously without success, to quarantine ships from the Netherlands and other plague-affected places. Another conspicuous resemblance is socioeconomic. In the United States, we've seen that covid-19 is disproportionately affecting poor people, as well as blacks and Latinos. Overall, these groups tend to have poorer health and less access to health care, and they are more likely to live in crowded, unhealthy conditions and to work in jobs that require them to come into close contact with others who may be infected. In New York for example, the death rate among blacks is twice as high as it is for whites; for Latinos, it is 60 percent higher. In Louisiana, blacks make up a third of the population but so far account for almost 60 percent of covid-19 deaths. About 5,000 meatpacking workers, and perhaps many more, have tested positive for the virus to date, largely because of a lack of safety measures and the industry's cramped and grueling working conditions. The situation 350 years ago in London was similar. During the epidemic, the London city government counted the dead, tracking how many people died of plague in each parish. This work was performed by "searchers of the dead," who were often older poor women. These parish lists, known as Bills of Mortality, were printed up and sold weekly, a kind of early version of Zip-code-by-Zip-code health reports from state health departments. Examining these lists, both 17th-century readers and historians have found that, no surprise, the poorest neighborhoods tended to have the highest death rates from the plague. The reasons for this are probably similar to the causes of today's disparities — the poor were already less healthy, lived in dense, unsanitary neighborhoods and did the city's dirty work. They also could not leave. Even without our current scientific knowledge, people knew that the disease moved from place to place. And once it reached English shores, people practiced social distancing as best they could, by getting away from the worst disease hot spots. Just as we are seeing today, those who could afford it left the cities for the countryside, where there was less disease; the classic medical advice of the time was "leave quickly, go far away and come back slowly." Even King Charles II left London, for Salisbury; when the disease showed up there, he went to Oxford. The poor, though, were largely stuck. They had no place to go, and they needed the work they were doing to survive. And just as they are now, rumors flourished. In recent weeks, hydroxychloroquine, diluted bleach and bananas have all been promoted as treatments, with little or no evidence backing them up. Conspiracy theories have proliferated, including the false claim that Bill Gates is somehow behind the pandemic. In 17th-century England, wigs became the focus of rumor. At the time, this was a big deal; elaborate powdered wigs were the height of fashion for both men and women. During the epidemic, however, people came to fear them as a source of disease — they were made from human hair, and who knew where it came from? Other rumors spread, too: Perhaps the two comets seen a few months apart had presaged the plague. Stories of women taken to plague hospitals against their will, and houses suddenly shut up, spread rapidly. All the while, city church bells rang incessantly to mark the passing of parishioners. Over the past few months, we've also seen officials and others use scapegoats to explain the pandemic. In the United States, China, where the virus originated, has been the most common target. Unsubtly, some leaders and media figures have called the pandemic the Chinese virus, or the Wuhan virus, after the city in which it first appeared. In recent months in the United States, there has been a sharp increase in anti-Asian bias, and 30 percent of people in a recent survey said they had witnessed an incident of such bias. Past outbreaks have been no different. During the bubonic plague of the 1300s, Jews were accused of poisoning wells and food supplies, and pogroms destroyed thousands of communities across Europe. Other European cities blamed prostitutes and ran them out of town when a plague threatened. In 1665 in England, those Dutch ships were all too easy to blame because the English were at war with the Dutch at the time. It's worth noting that these ways of thinking have recurred more recently: At the turn of the 20th century in the United States, tuberculosis was called the "Jewish disease," and Italian immigrants were blamed for outbreaks of polio. By early 1666, the outbreak had abated, to the point that the king and other well-off Londoners returned. Life slowly returned to normal. For reasons that remain mysterious, this was the last large outbreak of bubonic plague in England. Today, as we face another disease, one that we still don't understand very well, 17th-century England reminds us that despite the enormous leaps we've made in science and technology, humans themselves remain in many ways the same: imperfect, not always rational and still deeply vulnerable to novel nasty microbes. Read more: |

| Coronavirus: Problems plague Oakland trailers housing homeless - Marin Independent Journal Posted: 29 May 2020 03:30 PM PDT  Three weeks after Oakland opened a trailer park to house homeless residents during the coronavirus pandemic, dozens of people have moved in — but some are complaining of electrical, water and safety issues that have sent two people to the hospital. Earlier this month, the city set up 67 trailers on a vacant lot near the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum to provide safe shelter for residents who don't have COVID-19, but whose age or pre-existing medical conditions put them at risk of developing severe symptoms if infected. The city expected to house up to 134 people in the trailers — which were provided by the state — and 84 people have moved in so far. But it hasn't been all smooth sailing, some residents say. The power at the trailer park went out last weekend — leaving residents roasting with no air conditioning, in metal trailers on an asphalt lot, during a major heatwave. Having no electricity also meant 43-year-old Gina Shook, who has COPD and respiratory failure, couldn't power the oxygen machine she needs to breathe. She checked into Highland Hospital earlier this week with shortness of breath and chest pains, and remained hospitalized Friday. "Because they had electrical issues that were not properly tended to, I'm the who paid for it," she said from her hospital room. "It made me sick." Operating the new trailer park ended up requiring more power than expected, according to Oakland spokeswoman Karen Boyd. But the site managers installed a generator and are working with PG&E to upgrade the electrical panel at the camp to provide a permanent fix. "The City and the on-site service providers are working urgently to address every maintenance concern at the new site," she wrote in an email. "In setting up a brand new facility from scratch so quickly, we expected adjustments and are working with residents and maintenance crews to address them." Power at the site was off and on for about five days, Shook said. Delbra Taylor, another resident, said while the lights in her trailer are on, she's still not able to run her air conditioner. That's less of a problem now that the weather has cooled off, but she worries what will happen during the next heatwave. But 68-year-old Taylor's biggest complaint is the trailers' lack of safety features. Each one has three steps leading up to the door, but no handrail. Taylor fell on those steps earlier this month and fractured her right arm. It's in a sling now, and is expected to take up to three months to heal. "It was the result of these trailers," she said. The bathrooms don't have safety railings in the showers, either, which makes Taylor nervous now that she only has one arm to support herself. For a community that is supposed to cater to sick and elderly residents, the lack of safety measures is concerning, she said. The city is working on adding handrails to the trailers, according to Boyd. "We're also working collaboratively with the trailer manufacturers to best modify units to ensure safety for each resident," she wrote in the email. Taylor also said the toilet and sink in her trailer leak, forcing her to put towels down each day to soak up the water. Despite the problems, the trailer is a step up from where Taylor was before — she spent six years living in her car next to a Denny's restaurant on Hegenberger Road. When the pandemic hit, East Oakland Collective put her up in a hotel room for a month. And when money for her room ran out, the organization got her on the list for the new trailer park. "It is better than a car. It really is," Taylor said. Shook also was living in a vehicle before moving into the trailer park. While her wife slept in the Lake Merritt community cabins — a temporary shelter for local homeless residents — Shook slept in her wife's truck, which she parked next to Laney College.Before the electrical issues, life in the trailer was pretty good, Shook said. "I have absolutely no problem going back," she said. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "plague" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment