HIV and AIDS: Causes, symptoms, treatment, and more

George Floyd's Death At The Hands Of Police Is A Terrible Echo Of The Past : Code Switch - NPR |

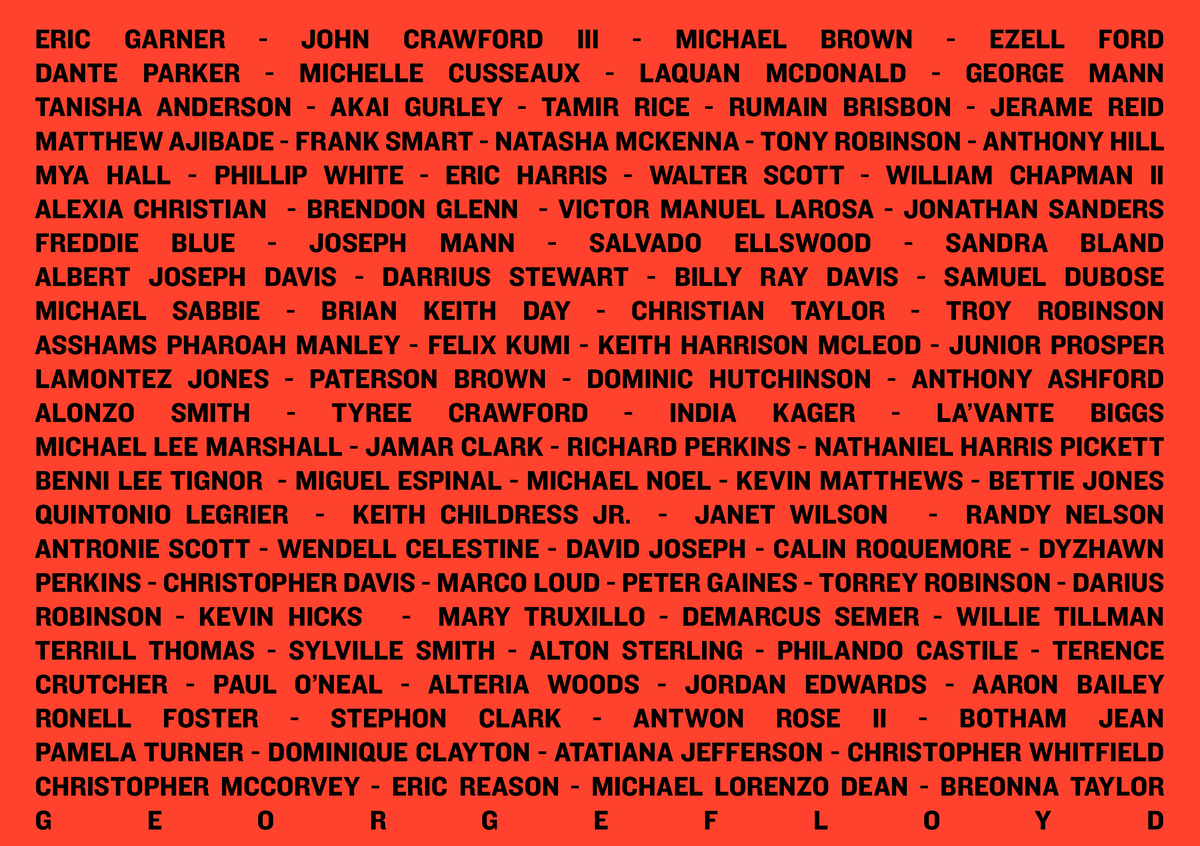

| George Floyd's Death At The Hands Of Police Is A Terrible Echo Of The Past : Code Switch - NPR Posted: 29 May 2020 07:19 PM PDT  The rate at which black Americans are killed by police is more than twice as high as the rate for white Americans. This is a non-comprehensive list of deaths at the hands of police in the U.S. since Eric Garner's death in July, 2014. LA Johnson/NPR hide caption  The rate at which black Americans are killed by police is more than twice as high as the rate for white Americans. This is a non-comprehensive list of deaths at the hands of police in the U.S. since Eric Garner's death in July, 2014. LA Johnson/NPRThe last few weeks have been filled with devastating news — stories about the police killing black people. At this point, these calamities feel familiar — so familiar, in fact, that their details have begun to echo each other. In July 2014, a cell phone video captured some of Eric Garner's final words as New York City police officers sat on his head and pinned him to the ground on a city sidewalk: "I can't breathe." On May 25 of this year, the same words were spoken by George Floyd, who pleaded for release as an officer knelt on his neck and pinned him to the ground on a Minneapolis city street. We're at the point where the verbiage people use to plead for their lives can be repurposed as shorthand for completely separate tragedies. Part of our job here at Code Switch is to contextualize and make sense of news like this. But it's hard to come up with something new to say. We covered the events in Ferguson in August of 2014 after Michael Brown was killed by the police, and we were in Baltimore after Freddie Gray's death in 2015. We covered the deaths of Eric Garner, Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, Delrawn Small. We've talked about what happens when camera crews leave cities still reeling from police violence. We've reflected on how traumatizing it can be for black folks to consume news cycles about black death, the semantics of "uprisings" versus "riots" and how #HousingSegregationInEverything shapes police violence. All of these conversations are playing out again. Since it's hard to come up with fresh insights about this phenomenon over and over over, we thought we'd look back to another time, back in 2015, when the nation turned its collective attention to this perpetual problem. We invited Jamil Smith, a senior writer at Rolling Stone, to read from an essay that he wrote at the New Republic more than five years ago, titled "What Does Seeing Black Men Die Do For You?" In it, he writes:

The essay is still hauntingly resonant today, as camera-phone videos of black people being killed by police circulate the internet. And it's a reminder that so much and so little has changed. Since January 1, 2015, 1,252 black people have been shot and killed by police, according to the Washington Post's database tracking police shootings; that doesn't even include those who died in police custody or were killed using other methods. We also spent time creating a (very non-comprehensive) list of names of black folks killed by the police since Eric Garner's death in 2014. Using resources including Mapping Police Violence and The Guardian's "The Counted" series, we read the names of people from across the country, of all ages. Some, like Tamir Rice and Sandra Bland, were familiar to us. But others were new — a reminder that many black deaths at the hands of police don't make it to national news. We wanted to learn more about each person's final moments before the police ended their lives. Here's some of what we learned: Eric Garner had just broken up a fight, according to witness testimony. Ezell Ford was walking in his neighborhood. Michelle Cusseaux was changing the lock on her home's door when police arrived to take her to a mental health facility. Tanisha Anderson was having a bad mental health episode, and her brother called 911. Tamir Rice was playing in a park. Natasha McKenna was having a schizophrenic episode when she was tazed in Fairfax, Va. Walter Scott was going to an auto-parts store. Bettie Jones answered the door to let Chicago police officers in to help her upstairs neighbor,who had called 911 in order to resolve a domestic dispute. Philando Castile was driving home from dinner with his girlfriend. Botham Jean was eating ice cream in his living room in Dallas, Tx. Atatiana Jefferson was babysitting her nephew at home in Fort Worth, Tx. Eric Reason was pulling into a parking spot at a local chicken and fish shop. Dominique Clayton was sleeping in her bed. Breona Taylor was also asleep in her bed. And George Floyd was at the grocery store. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "black death" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment