Childhood TB (part 2): presentation and diagnosis

“If you want to feel better about this pandemic, consider the Black Plague - New York Post” plus 1 more |

| If you want to feel better about this pandemic, consider the Black Plague - New York Post Posted: 30 Mar 2020 05:48 PM PDT  No one would make light of a pandemic that has already cost so much in terms of death, suffering and treasure — especially since there is undoubtedly so much more to come. But still, it must be said that if we are to have a pandemic, the early 21st century is the best time in all human history to have one. They used to be common. Yellow fever, malaria, cholera and other deadly diseases swept through American cities over and over in the early years of the nation, and there was little that doctors could do to help the victims. Their patients lived or died as fate and their immune systems would have it. With the birth of epidemiology as a science in the mid-19th century, however, these diseases rapidly abated as physicians learned what was needed to prevent them from spreading via insects, contaminated water and other vectors. The diseases that spread directly from human to human through the respiratory route, such as flu and the coronavirus, however, were much harder to prevent. The Spanish flu of 1918-1919 took at least 50 million lives worldwide. But the enormous medical advances of the last century in terms of vaccines, tests, drugs and technology increased the ability to contain the spread of these diseases — and help victims survive them — by several orders of magnitude. So while the coronavirus pandemic's effects will be painful, to say the least, dealing with them is well within our power. That wasn't always the case with earlier epidemics. To imagine what pandemics were like in a world where medicine was nothing more than a hodgepodge of untested, contradictory and mostly crackpot theories, just consider the most infamous and perhaps the most deadly of them all, the Black Death of medieval Europe, caused by bubonic plague. It originated in Asia and spread to Europe via Genoese ships coming from Crimea beginning in 1347. Traveling through both land and maritime trade routes, the plague swept across Europe in a great left hook. Beginning in Italy, it reached England in 1348, Scotland and most of Scandinavia in 1350, from which it spread eastward toward Russia, before finally petering out in 1353. It left a devastated continent in its wake. At least one-third of the population died in those terrible years. It would be two centuries before the population again reached pre-plague levels. Florence, Italy, particularly hard-hit, wouldn't fully recover demographically until the 19th century. In the cities, corpses lay untended in the streets or were buried in mass graves. In the countryside, whole villages were deserted — England alone saw at least a thousand villages simply disappear — and livestock wandered at will, free for the taking. The economic effects of the plague can't be overstated. Indeed, they began the transition of Europe from the medieval to the modern era. The land remained, of course, and fell into the hands of fewer landlords, for the plague largely hit all levels of society equally, not hitting the poor especially hard as other epidemics often did. But the labor needed to work the land was now much scarcer. The economic balance of power between lords and peasants, therefore, shifted sharply in favor of the peasants. With landlords desperate for workers, peasants were able to go where the best deal was to be had. Serfdom began to fade away, as landlords converted labor services into wages or rents. In the cities, craftsmen were able to command much higher wages from the guildsmen. This reduced class distinctions, as the standard of living among workers rose sharply. Suddenly, they were able to afford better furniture, household goods and clothes. Indeed, so many people began to wear linen underwear that the price of paper declined as its source material — rags — increased. The labor shortage also led to a search for labor-saving devices. Productivity per capita rose an astonishing 30 percent in the next few decades. The plague would return again and again to Europe until the mid-17th century but never as ferociously as in the time of the Black Death. Today, plague is a trivial disease, easily cured by antibiotics, proof that while we are going through a bad time, we live in medically very good times, indeed. John Steele Gordon writes for Commentary. Share this: |

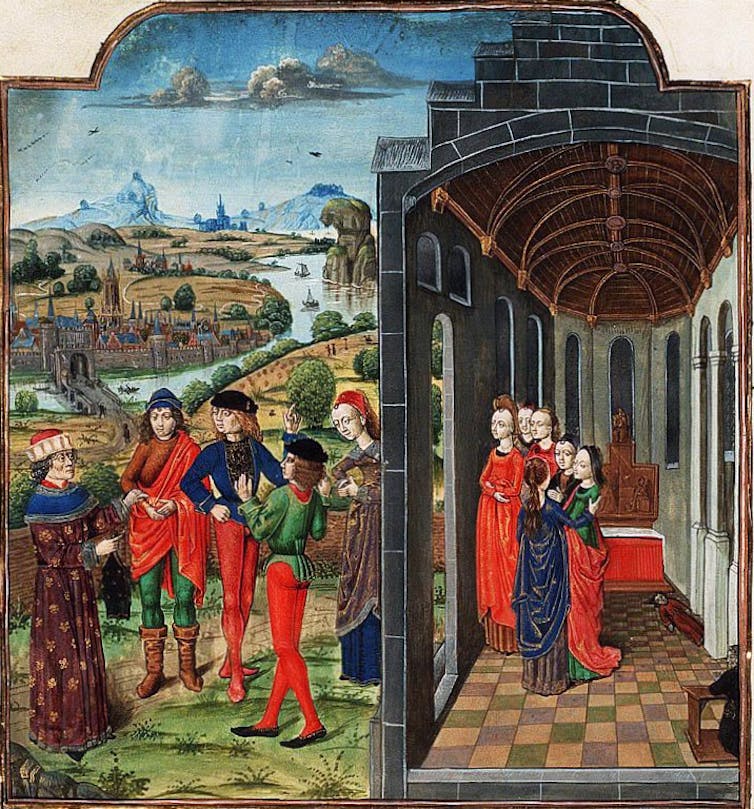

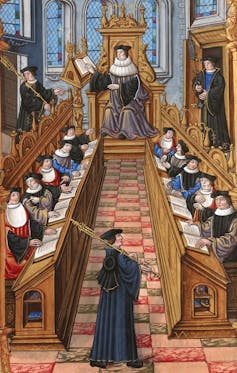

| How the medieval writers coped during the Black Death - The Conversation CA Posted: 31 Mar 2020 05:49 AM PDT A plague of serious proportions is ravaging the world. But not for the first time. From 1347-51, the Black Death killed anywhere from one-tenth to one-half (or more) of Europe's population. One English chronicler, Thomas Walsingham, noted how this "great mortality" transformed the known world: "Towns once packed with people were emptied of their inhabitants, and the plague spread so thickly that the living were hardly able to bury the dead." As death tolls rose at exponential rates, rents dwindled, and swaths of land fell to waste "for want of the tenants who used to cultivate it…."  As a medieval historian, I've been teaching the subject of plague for many years. If nothing else, the feelings of panic between the Black Death and the COVID-19 pandemic are reminiscent. Like today's crisis, medieval writers struggled to make sense of the disease; theories on its origins and transmission abounded, some more convincing than others. Whatever the result, "… so much misery ensued," wrote another English author, it was feared that the world would "hardly be able to regain its previous condition." A disease without bordersMedieval writers produced a variety of answers for the plague's origins. Gabriele de Mussis' Historia de Morbo attributed the cause to "the mire of manifold wickedness," the "numberless vices," and the "limitless capacity for evil" exhibited by an entire human race no longer fearing the judgement of God. Describing its eastern origins, he further noted how the Genoese and Venetians had imported the disease to western Europe from Caffa (modern-day Ukraine); "carrying the darts of death," disembarking sailors at these Italian port-cities unwittingly spread the "poison" to their relations, kinsmen and neighbours.  Containing the disease seemed nearly impossible. As Giovanni Boccaccio wrote about Florence, the outcome was all the more severe as those suffering from the disease "mixed with people who were still unaffected …" Like a "fire racing through dry or oily substances," healthy persons became ill. Possessing the power to "kill large numbers by air alone," through breath or conversation, it was thought, the plague "could not be avoided." Looking for a cureScholars worked tirelessly to find a cure. The Paris Medical Faculty devoted its energies to discovering the causes of these amazing events, which even "the most gifted intellects" were struggling to comprehend. They turned to experts on astrology and medicine about the causes of the epidemic.  On the pope's orders, anatomical examinations were carried out in many Italian cities "to discover the origins of the disease." When the corpses were opened up, all victims were found to have "infected lungs." Not content with lingering uncertainty, Parisian masters turned towards ancient wisdom and compiled a book of existing philosophical and medical knowledge. Yet they also acknowledged the limitations in finding a "sure explanation and perfect understanding," quoting Pliny to the effect that "some accidental causes of storms are still uncertain, or cannot be explained." Self-isolation and travel bansPrevention was critical. Quarantine and self-isolation were necessary measures. In 1348, to prevent the illness from spreading through the Tuscan region of Pistoia, strict fines were enforced against the movement of peoples. Guards were placed at the city's gates to prevent travellers entering or leaving. These civic ordinances stipulated against importing linen or woollen cloths that might carry the disease. Demonstrating similar sanitation concerns, bodies of the dead were to remain in place until properly enclosed in a wooden box "to avoid the foul stench which comes from dead bodies"; moreover, graves were dug "two and a half arms-lengths deep." Butchers and retailers nevertheless remained open. And yet a number of regulations were imposed so that "the living are not made ill by rotten and corrupt food," with further bans to minimize the "stink and corruption" considered harmful to Pistoia's citizens. Community response and resolveAuthorities responded in different ways to the outbreak. Recognizing the plague's arrival by ship, the people of Messina "expelled the Genoese from the city and harbour with all speed." In central Europe, foreigners and merchants were banished from the inns and "compelled to leave the area immediately." These were severe measures, but seemingly necessary given the varied social reaction to plague. As Boccaccio famously recounted in his Decameron, the whole spectrum of human behaviour ensued: from extreme religious devotion, sober living, self-isolation and a restricted diet to warding off evil through heavy drinking, singing and merrymaking.  The fear of contagion eroded social customs. The number of dead grew so high in many regions that proper burials and religious services became impossible to perform: new religious customs emerged pertaining to preparing for and presiding over death. Families were changed. An account from Padua mentions how "wife fled the embrace of a dear husband, the father that of a son and the brother that of a brother." Ultimately, there is a human element to plague too often lost in the historical record. Its influence should not be underestimated or forgotten. The modern response to pandemic evokes a similar community response. Different in scope and scale, and indeed in medical practice, administrative and public health actions remain critical. But in 2020, we are not, as Boccaccio lamented, seeing the law and social order break down. Essential duties and responsibilities are still being carried out. Against our own 21st-century plague, wisdom and ingenuity are prevailing; citizens hang on "the advice of physicians and all the power of medicine," which unlike the 14th century, is anything but "profitless and unavailing." |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "black death" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment