Lung microbiome: new insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases

“California has its first case of plague in 5 years. How likely are you to catch it? - CBS News” plus 1 more |

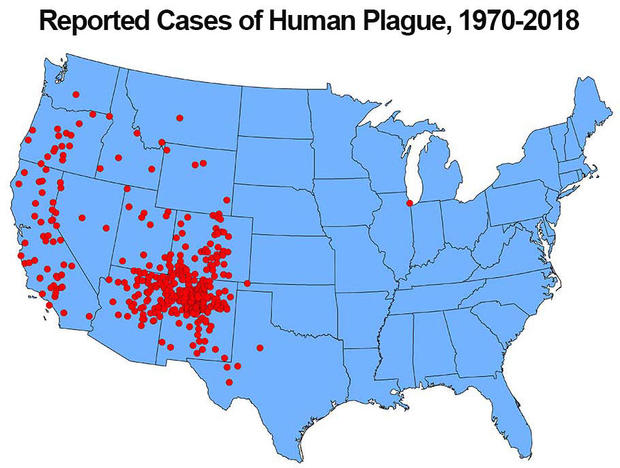

| California has its first case of plague in 5 years. How likely are you to catch it? - CBS News Posted: 20 Aug 2020 12:00 AM PDT In the Middle Ages, the plague caused tens of millions of deaths in Europe in a series of outbreaks known as the Black Death. And while it's extremely rare in modern times, the deadly bacterial infection is still around today — but how likely are you to catch it? This week, California reported its first case of plague in five years. The patient, a resident of the South Lake Tahoe area, is said to be recovering at home. And in July, a 15-year-old boy in western Mongolia died of bubonic plague that he contracted from an infected marmot. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a total of 3,248 cases were reported worldwide between 2010 and 2015, resulting in 584 deaths. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar and Peru were the most affected countries. Reports of the plague can be scary — but experts say there's little cause for concern in most cases. What is the plague?Plague is a disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which affects humans and other mammals. There are three types of plague: bubonic, septicemic and pneumonic. Bubonic is the most common form, accounting for more than 80% of cases in the U.S. Pneumonic plague is the most serious. Many animals can get the plague, including rock squirrels, wood rats, ground squirrels, prairie dogs, chipmunks, mice, voles, and rabbits. It's typically transmitted from animals to humans, with much more rare cases of the disease being spread person to person. How is the plague transmitted?The plague is transmitted through fleas that live on rodents, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). People typically get bubonic or septicemic plague after they are bitten by a flea that is carrying the bacterium. Humans may also contract the disease when handling an animal that is infected, resulting in either bubonic or septicemic plague. In some cases, people can catch the pneumonic plague when an infected person coughs, causing infectious droplets to spread. This is the only way for the plague to spread between people. Cats and dogs can both lead to human infections. Cats are particularly susceptible to getting sick, and have been linked to several cases of human plague in the U.S. via respiratory droplets in recent decades. What are the symptoms of the plague?A key symptom of the bubonic plague is buboes: painful, swollen lymph nodes in the groin or armpits. Other symptoms include fever, weakness, coughing and chills. Patients with septicemic plague develop fever, chills, extreme weakness, adnominal pain, shock and possibly internal bleeding. Skin and other tissues, especially on fingers, toes, and the nose may turn black and die. Patients with pneumonic plague — the most serious form of the disease — develop fever, headache, weakness, pneumonia, shortness of breath, chest pain, cough and sometimes bloody or watery mucous. Pneumonia could cause respiratory failure and shock. What regions are most affected by the plague?The plague was first introduced to the U.S. in 1900, from steamships carrying infected rats. The last urban outbreak of rat-associated plague in the U.S. was in Los Angeles between 1924 and 1925. "The risk relates to both the prevalence of plague where you live and the types of exposures you have to rodents and fleas," Dr. Erica S. Shenoy, a medical director and associate chief at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, told CBS News on Wednesday. In the U.S., an average of seven plague cases per year are reported to the CDC from the western part of the country, particularly in rural areas. Arizona, California, Colorado, Oregon, Nevada and New Mexico are the most affected states, where the bacterium is not uncommon.  Dr. Robyn R.M. Gershon, a professor and program director at the NYU School of Global Public Health, told CBS News on Wednesday that only people who live in an area where the disease is common need to be concerned. "With proper precautions, you can avoid contact with possibly infected fleas," Gershon said. "If you do get infected, there is very good treatment available with antibiotics. The only risk is that the infection will not be diagnosed promptly, which can then lead to more serious disease." There have been five cases in the U.S. so far this year. A significantly higher portion of cases are reported in parts of Africa and Asia, but it can be found on all continents except Oceania. How is plague treated?"Infections in humans are rare," Dr. Gershon said. "Most recover, although occasionally there is a death related to some of the more severe forms the disease can take." Early diagnosis and treatment are essential for survival and reducing future complications. Common antibiotics, such as streptomycin, can prevent complications or in some cases death, if administered soon after symptoms present themselves. Untreated bubonic or septicemic plague can develop in the pneumonic plague, which spreads to the lungs. The bubonic type has a case-fatality ratio of 30% to 60%, according to the WHO. Pneumonic plague, when left untreated, is always fatal within 18 to 24 hours. "The key for clinicians is suspecting plague in the first place, obtaining the right specimens to make a diagnosis, and initiating treatment even before the diagnosis is made — as soon as you suspect it, you should start treating while the evaluation is ongoing," Shenoy said. There is not currently a vaccine for the plague available in the U.S., but researchers are investigating several options to try to eradicate it. No vaccines are expected to be commercially available in the near future. How can I protect myself from the plague?"It's important that individuals take precautions for themselves and their pets when outdoors, especially while walking, hiking and/or camping in areas where wild rodents are present," California's El Dorado County Public Health Officer Dr. Nancy Williams said this week. "Human cases of plague are extremely rare but can be very serious." Low levels of the bacterium persist in certain rodent communities without causing a significant die-off, making the disease difficult to fully eradicate. Eliminating rodents is a key prevention method. Removing nesting places — brush, rock, trash, firewood and possible food supplies — around homes and workplaces will help. If you come across a sick or dead animal, do not touch it yourself, especially without gloves. Contact your local health department regarding disposal. Using insect repellent that contains DEET could prevent flea bites while camping, hiking, or during other outdoor activities. It is also important to treat dogs and cats for fleas on a regular basis, and the CDC advises not sleeping in the same bed with pets that roam free in endemic areas. |

| Worse Than COVID? The Tasmanian Devil's Contagious Cancer - PLoS Blogs Posted: 26 Nov 2020 06:19 AM PST  It's hard to imagine anything worse than the horrors at our hospitals right now. But in a recent JAMA webinar, Nicholas Christakis, Yale Sterling Professor, put the fatality rate of COVID-19 into historical perspective: "Bad as it is, the fatality rate, at .5-.8%, isn't as bad as bubonic plague, which would kill 50% of a population in a few months. Or Ebola at 80%. Or smallpox at 95%. It could have been so much worse." He's a physician, scientist, public health expert, and sociologist. It's an unusual viewpoint to downplay the horror of this moment in time, but Dr. Christakis's new book, "Apollo's Arrow: The Profound and Enduring Impact of Coronavirus on the Way We Live," takes a broader look. He said at the webinar: "This way we're living right now seems alien and unnatural, but plagues aren't new to our species, just new to us. People have struggled with plagues for thousands of years. The Iliad opens with a plague on the Greeks and Apollo reigns down, the Bible, Shakespeare. What's different about our current experience is our time in the crucible happens to be occurring when we can create a vaccine in real time. The fact that we have the technological capability to respond within a year with phase 3 trials of active agents is mind-boggling." We aren't the only species subject to unseen pathogens, including the viruses that aren't even cells or technically alive, just borrowed bits of our own genomes turned against us. With Dr. Christakis's wider view in mind, I noticed a new article about an infectious cancer in Tasmanian devils. It combines two terrors. A Transmissible Cancer A Tasmanian devil, the size of a small dog, is a carnivorous marsupial. The endangered animals live only in the state of Tasmania, an island off the southern coast of eastern Australia. Introduction of dingoes to the mainland four centuries ago is thought to have driven the devils to their disappearing island home. The full scientific name of the Tasmanian devil is Sarcophilus harrisii, perhaps best knows as Looney Tunes character Taz. The cancer "devil facial tumor 1" (DFT1) first appeared in 1996 and has been rocketing through the population ever since. DFT1 hideously disfigures the animal, with large tumors around the head and in the mouth. Normal biting behavior transmits it. In a new host the tumor explodes, cells rapidly dividing, easily overriding the animal's immune response. Worse, live cancer cells go from animal to animal, as if the cells are themselves infectious organisms, pathogens. But this isn't the same as passing a sexually transmitted infection from person to person, such as HPV, which is a virus that predisposes to cervical cancer. DFT1 is deadly, decimating the Tasmanian devil population and driving its extinction. Breeders are trying to establish a colony in New South Wales to save it. Only three naturally-occurring transmissible cancers are known. Joining DFT1 are canine transmissible venereal tumor and a widespread cancer of soft-shell clams, according to the Transmissible Cancer Group in the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Cambridge. Their study just published in PLOS Biology, with colleagues from Australia and France, reveals the odd genomes of the cancer cells that cause DFT1. Exploring Strangely Stable Genomic Changes "In cancer, the genome is shot to hell," a prominent researcher once told me. Cancer cells, even within an individual, often display an array of the ways that DNA and chromosomes can go off-kilter as they lose control of their division cycle. Healthy human cells growing in culture famously divide 40 to 60 times, the so-called Hayflick limit. Cancer cells, given enough space and nutrients, hormones, growth factors, and transcription factors, divide forever. A cancer cell that's been in a body longer has more mutations than a more recently generated one. Mutations accrue, their patterns holding the history, the narrative, of that particular cancer in that particular body. The utter constancy of the genome changes in facial tumor cells in the devils, echoed in laboratory culture, is puzzling. The cancer genomes are much more alike, from devil to devil, than are the cancer cells in a single human. What's going on? The genomic similarity of the tumors in different animals suggests that the disease began in a single "founder" Tasmanian devil, transmitted by the biting behavior. More typically, a cancer just vanishes when the host dies. The constancy, the sameness, in evolutionary terms means that whatever the persistent genome is, it offers an advantage that somehow stabilizes the cancer cells so they survive and thrive, through body after body after body – but whatever that advantage is, isn't clear. Calling the infectious cancer "a natural experiment for observing the evolution of cancer cell adaptation," the researchers analyzed the genomes of cells from 648 DFT1 tumors, collected from 2003 through 2018. Over that time the tumors mutated into five groups, or clades, dropping to three. Mapping the clades with geography showed how the cancer has spread, in the diseased devils, throughout their shrinking habitat. The findings remind me of a recent paper in Science, "Transmission heterogeneities, kinetics, and controllability of SARS-CoV-2," that traces the early spread of COVID-19 in China. The facial cancer cell genomes plucked from Tasmanian devils have several oddities. Cells from devils sampled decades and kilometers apart are remarkably similar. When cultured in the laboratory, the cancer cells proceed through the same choreography of genomic mayhem as they do on Tasmanian devil faces. Whatever is happening in the animals is recapitulated in glassware. "DFT1 has acquired relatively few mutations during its thirty-year history. This research illustrates how a comparatively simple and stable cancer can colonize diverse niches and devastate a species," said study leader Elizabeth Murchison. CODA Is there a link to, or message about, COVID-19 in the plight of the Tasmanian devils? Probably not; sometimes I'm just drawn to biological mysteries, and this one reverberated against the constant hum in my brain that comes from reading the technical papers on the pandemic nearly every waking moment. But I can't help making comparisons. Here's one. We humans are capable of reasoning, of foreseeing consequences. We can choose to alter our risk of contracting COVID-19 with behavior – mask-wearing, social distancing, testing, avoiding situations that take us near others. As far as I know, carnivorous marsupials rely more on instinct than reasoning. And so Tasmanian devils will keep on biting, and keep on dying, as the strong and persistent cancer cells flit from animal to animal, easily taking root and flourishing, until their hosts simply vanish. Perhaps we will learn something about ourselves from their unusual cancer. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "how is plague transmitted" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment