A systematic framework for understanding the microbiome in human health and disease: from basic principles to clinical translation

“From the plague to MERS: A brief history of pandemics - Aljazeera.com” plus 1 more |

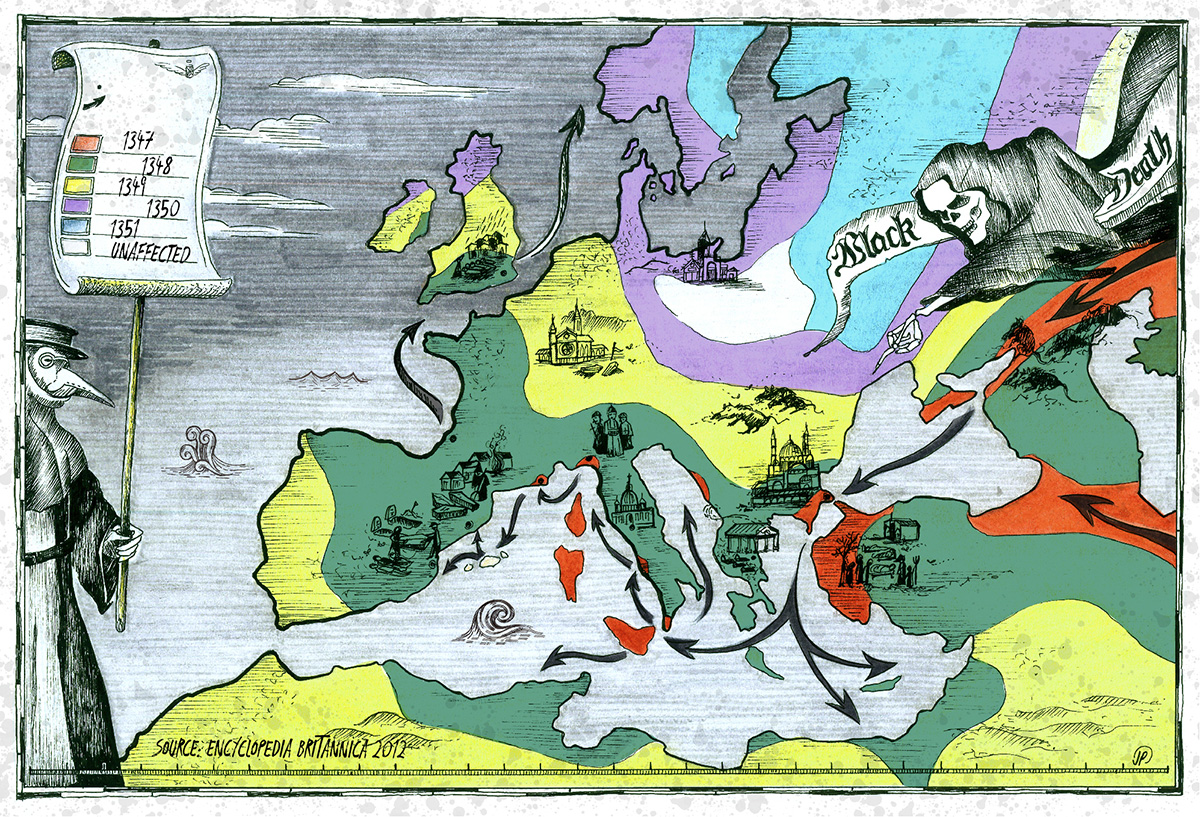

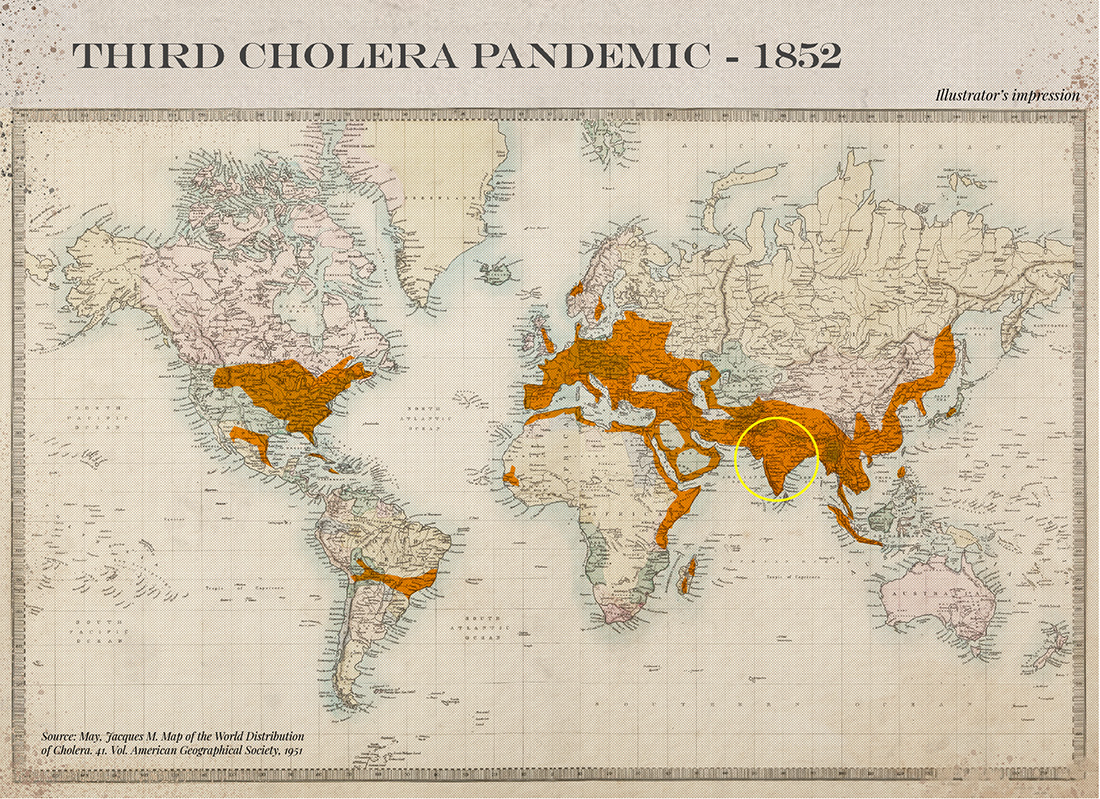

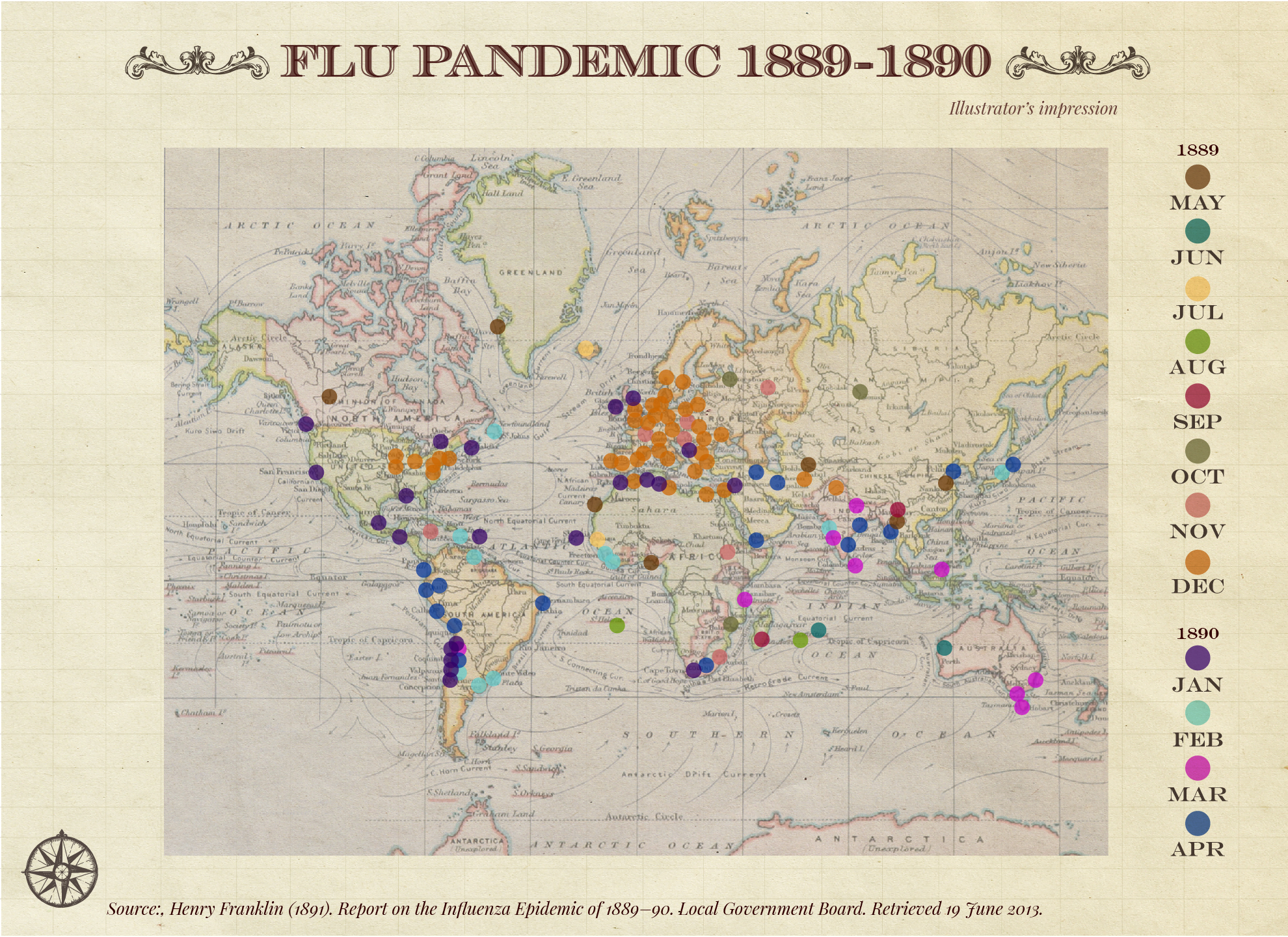

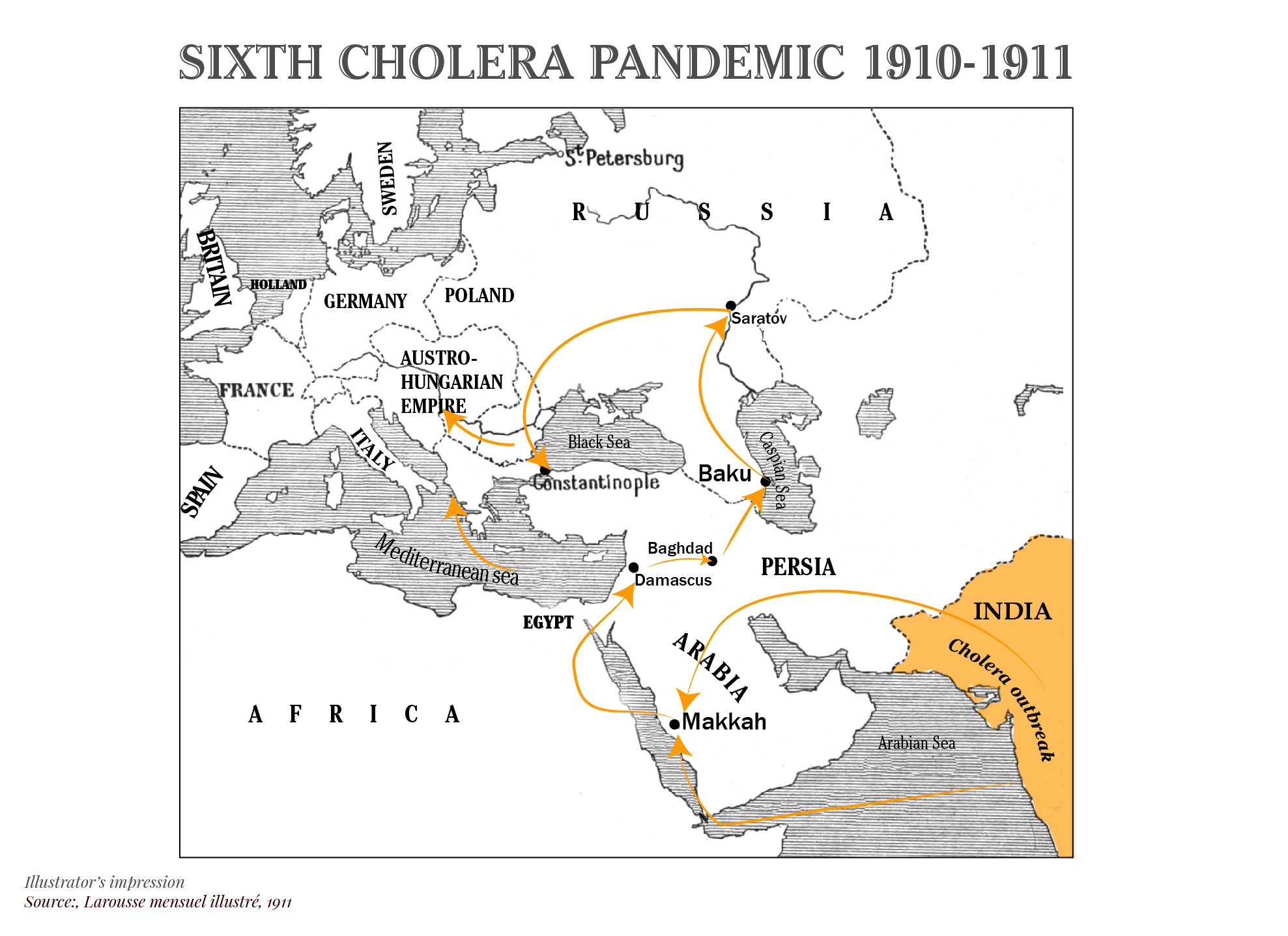

| From the plague to MERS: A brief history of pandemics - Aljazeera.com Posted: 01 Jun 2020 01:33 AM PDT On March 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the new coronavirus - which was first reported in the Chinese city of Wuhan late last year - a pandemic. As of May 31, there were more than 6.1 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, according to data collected by Johns Hopkins University, while the number of registered deaths worldwide stood at nearly 371,000. To date, there is no vaccine or known treatment for the new coronavirus, officially known as SARS-CoV-2. Some of the most basic defences against it include frequent and thorough handwashing with soap and water, physical distancing and self-isolation. These recommendations have also been the prescribed measures to contain the spread of other highly contagious diseases in the past. The practice of quarantine for contagious diseases was mentioned in the Canon of Medicine written by Persian polymath Ibn Sina (980-1037), better known in the West as Avicenna, and published in 1025. The word quarantine comes from the Italian "quaranta giorni", which translates to 40 days. Here is a brief look at some of those past pandemics.  The Plague of Justinian (541-549)Death Toll: Approximately 30-50 million Cause: Bubonic Plague This was the first-ever recorded incident of the plague. Named after the Byzantine emperor, Justinian I, who caught the disease but recovered, it was spread to humans by rodents harbouring fleas that carried the bacterium, Yersinia pestis. The rats travelled on grain ships and in grain carts. As the political and commercial centre of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) was particularly hard hit. According to ancient historians, the pandemic killed up to 10,000 people a day there, although modern historians say the number may have been closer to 5,000. But it was not limited to Constantinople. It spread throughout the empire, facilitated by war and trade, killing nearly 25 percent of the population. It returned every 12 years or so until around 750, eventually wiping out half of Europe's population (around 100 million people).  The Black Death (1346-1353)Death Toll: Approximately 75-200 million Cause: Bubonic Plague The Black Death ravaged Europe, Africa and Asia, killing anywhere between 75 million and 200 million people - making it the deadliest disease outbreak in recorded history. Like the Plague of Justinian, it was also caused by the bacterium, Yersinia pestis, carried by rats. Ships carrying the rats enabled it to spread between continents. It was supposedly named the Black Death because of the black spots that formed on the skin of the infected. According to some accounts, the first outbreak of the Black Death in Europe took place in Caffa, on the Crimean Peninsula. In 1346, this important trading post was besieged by the Mongol army, which had conquered lands throughout Asia. Many of the soldiers, however, were infected with the plague. When they succumbed to it, the army catapulted their corpses over the city walls, causing people living inside the city to become infected.  The Third Cholera Pandemic (1852-1860)Death Toll: Approximately 1 million Cause: Cholera According to the WHO, there have been seven cholera epidemics. The one that had the greatest global impact was the third, in 1852. It originated in India before spreading through the rest of Asia and parts of Europe, North America and Africa. Cholera is caused by eating food or drinking water contaminated with the bacterium, Vibrio cholera. It can result in acute diarrhoeal disease that can kill within hours if left untreated. According to the WHO, there are still 1.3 million to four million cases of cholera each year, with between 21,000 and 143,000 fatalities.  Flu Pandemic (1889-1890)Death Toll: At least 1 million Cause: Influenza A subtype H3N8 Considered the last great pandemic of the 19th century, this particular strain of influenza was known as the "Asiatic Flu" or "Russian Flu", likely because it originated in the Central Asian region of the Russian Empire. The pandemic spread quickly, aided by the existence of modern forms of transport, like railroads, and transatlantic travel by boat. In fact, it took just four months to circle the planet, peaking in the US 70 days after its original peak in St Petersburg.  The Sixth Cholera Pandemic (1899-1923)Death Toll: 800,000 Cause: Cholera Cholera went through several surges, and its sixth incarnation in 1910, like the ones before it, originated in India. It killed hundreds of thousands of people before spreading to various parts of the Middle East, North Africa, Europe and Russia. Cholera transmission is closely linked to inadequate access to clean water and sanitation facilities. It takes between 12 hours and five days for a person to show symptoms after consuming contaminated food or water.  Flu Pandemic (1918-1919)Death Toll: Approximately 20-100 million Cause: Influenza H1N1- Avian origin The first identified cases of this particular strain of influenza were recorded in the spring of 1918 among US soldiers during WWI, before spreading worldwide and infecting at least one-third of the global population. Although the death toll is unknown, many estimates put it at more than 50 million and some as high as 100 million, making it the deadliest pandemic since the Black Death. In the US, it was dubbed the "Spanish flu", although researchers could not identify the geographical origin of the disease. However, cases of the illness were widely reported in Spain, which was not involved in WWI and therefore, not subjected to war-time news blackouts, possibly creating a false impression that it originated there. What was particularly significant about this outbreak was its effect on healthy adults, unlike prior outbreaks where the immunocompromised and juveniles had been more susceptible. Without any vaccine, this pandemic had two waves. The initial wave being milder than the second. Returning soldiers contributed to the second wave. Communities imposed quarantines, the wearing of masks and bans on public gatherings as a way of combatting the pandemic. It is thought that these measures, combined with people developing immunity to it, helped to end the pandemic, although there is also a theory that the virus mutated rapidly into a less lethal strain, resulting in a sharp drop in infections and deaths.  Asian Flu (1956-1958)Death Toll: At least 1.1 million Cause: Influenza A - H2N2 subtype The first case of the Asian Flu was identified in China in 1956. From there, it travelled to Singapore, Hong Kong and the US. There were also reports of it spreading to India in 1957. Studies suggested the pandemic originated from strains of avian and human influenza viruses. Symptoms, which included weakness in the legs, chills, a sore throat, running nose and cough, appeared soon after exposure to the virus. There were two waves of this outbreak, but the spread of the infection slowed following the development of a vaccine in August 1957.  Hong Kong Flu Pandemic (1968)Death Toll: Approximately 1 million Cause: Influenza A - H3N2, subtype of H2N2 The first reported case of this pandemic was in July 1968 in Hong Kong. Outbreaks occurred in Singapore and Vietnam and within 12 weeks spread to other parts of the world, as far as Africa and South America. In the US, an estimated 100,000 died. The mutation of the earlier Asian flu in 1956 possibly gave rise to the H3N2 variation, in a process called the antigenic shift, in which the virus mutates. The death rate was significantly lower than in previous influenza outbreaks, with a case-fatality ratio below 0.5 percent. It is possible that people who were exposed to the earlier pandemic became immune to this particular virus. Improved medical care and the availability of antibiotics, for secondary bacterial infections, have also been cited as factors for the slower spread of the disease. The H3N2 virus is still in circulation today as the seasonal influenza A virus.  HIV/Aids Pandemic (1981-)Death Toll: 32 million Cause: Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) that attacks the cells that help the body fight infections. If left untreated, it can lead to the disease, AIDS. HIV attacks and destroys a type of white blood cell in the immune system, called the CD4 cell or T-Helper, and makes copies of itself inside these cells. As it destroys more of these cells and makes more copies of itself, the immune system is gradually weakened - making it difficult for the body to fight off other infections. The last stage of a weakened immune system is AIDS. AIDS was first reported in 1981. Human-to-human transmission can happen through unprotected sexual contact, sharing needles with an HIV-infected person and transfusions of contaminated blood. Almost one million people die each year because of AIDS. According to the WHO, which refers to it as a global epidemic rather than a pandemic, in certain regions of Africa, which remain the most affected, one in every 25 people is living with HIV, accounting for more than two-thirds of the global HIV count.  Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) (2002-2003)Death Toll: 774 Cause: SARS-CoV According to the US CDC, SARS-CoV is thought to be a strain of the coronavirus from an as-yet-uncertain animal reservoir, perhaps bats, that spread to other animals (civet cats) and first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002. SARS-CoV spread to at least 26 countries and infected more 8,000 people, although the death toll was considered very low compared to other pandemics. Symptoms are influenza-like and include fever, headache, diarrhoea and shivering. Even at the height of the pandemic, in 2003, the overall risk of transmission was low. Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan were hit the hardest, prompting them to establish medical protocols in anticipation of future pandemics.

|

| Pandemics come and go. The way people respond to them barely changes. - The Washington Post Posted: 07 May 2020 08:25 AM PDT  I'm a historian who studies medicine in 17th century England, and lately I've been thinking about one particular pandemic: the bubonic plague that struck Britain in 1665, killing at least 200,000 people, including about 15 percent of the population of London. As we struggle to deal with the coronavirus pandemic, what strikes me most is how similar our experiences and responses are to those of the people living in England more than three centuries ago. No Zoom, no Instacart, no "Tiger King," but human behavior in the face of plague seems remarkably familiar. Just as today, a global economy was a key driver of the English epidemic. Bubonic plague, which is bacterial rather than viral, is typically spread to humans by fleas who have fed on the blood of infected rats. Earlier plague epidemics — such as the Black Death of the 1300s, which may have wiped out half the population of Europe — came to Europe via merchants traveling back from Asia along the Silk Road. In the same way, contemporary observers reported that the 1665 epidemic may have been brought to London by Dutch trading ships; the epidemic had already spread there a year earlier. In the months before it reached England, authorities had tried, obviously without success, to quarantine ships from the Netherlands and other plague-affected places. Another conspicuous resemblance is socioeconomic. In the United States, we've seen that covid-19 is disproportionately affecting poor people, as well as blacks and Latinos. Overall, these groups tend to have poorer health and less access to health care, and they are more likely to live in crowded, unhealthy conditions and to work in jobs that require them to come into close contact with others who may be infected. In New York for example, the death rate among blacks is twice as high as it is for whites; for Latinos, it is 60 percent higher. In Louisiana, blacks make up a third of the population but so far account for almost 60 percent of covid-19 deaths. About 5,000 meatpacking workers, and perhaps many more, have tested positive for the virus to date, largely because of a lack of safety measures and the industry's cramped and grueling working conditions. The situation 350 years ago in London was similar. During the epidemic, the London city government counted the dead, tracking how many people died of plague in each parish. This work was performed by "searchers of the dead," who were often older poor women. These parish lists, known as Bills of Mortality, were printed up and sold weekly, a kind of early version of Zip-code-by-Zip-code health reports from state health departments. Examining these lists, both 17th-century readers and historians have found that, no surprise, the poorest neighborhoods tended to have the highest death rates from the plague. The reasons for this are probably similar to the causes of today's disparities — the poor were already less healthy, lived in dense, unsanitary neighborhoods and did the city's dirty work. They also could not leave. Even without our current scientific knowledge, people knew that the disease moved from place to place. And once it reached English shores, people practiced social distancing as best they could, by getting away from the worst disease hot spots. Just as we are seeing today, those who could afford it left the cities for the countryside, where there was less disease; the classic medical advice of the time was "leave quickly, go far away and come back slowly." Even King Charles II left London, for Salisbury; when the disease showed up there, he went to Oxford. The poor, though, were largely stuck. They had no place to go, and they needed the work they were doing to survive. And just as they are now, rumors flourished. In recent weeks, hydroxychloroquine, diluted bleach and bananas have all been promoted as treatments, with little or no evidence backing them up. Conspiracy theories have proliferated, including the false claim that Bill Gates is somehow behind the pandemic. In 17th-century England, wigs became the focus of rumor. At the time, this was a big deal; elaborate powdered wigs were the height of fashion for both men and women. During the epidemic, however, people came to fear them as a source of disease — they were made from human hair, and who knew where it came from? Other rumors spread, too: Perhaps the two comets seen a few months apart had presaged the plague. Stories of women taken to plague hospitals against their will, and houses suddenly shut up, spread rapidly. All the while, city church bells rang incessantly to mark the passing of parishioners. Over the past few months, we've also seen officials and others use scapegoats to explain the pandemic. In the United States, China, where the virus originated, has been the most common target. Unsubtly, some leaders and media figures have called the pandemic the Chinese virus, or the Wuhan virus, after the city in which it first appeared. In recent months in the United States, there has been a sharp increase in anti-Asian bias, and 30 percent of people in a recent survey said they had witnessed an incident of such bias. Past outbreaks have been no different. During the bubonic plague of the 1300s, Jews were accused of poisoning wells and food supplies, and pogroms destroyed thousands of communities across Europe. Other European cities blamed prostitutes and ran them out of town when a plague threatened. In 1665 in England, those Dutch ships were all too easy to blame because the English were at war with the Dutch at the time. It's worth noting that these ways of thinking have recurred more recently: At the turn of the 20th century in the United States, tuberculosis was called the "Jewish disease," and Italian immigrants were blamed for outbreaks of polio. By early 1666, the outbreak had abated, to the point that the king and other well-off Londoners returned. Life slowly returned to normal. For reasons that remain mysterious, this was the last large outbreak of bubonic plague in England. Today, as we face another disease, one that we still don't understand very well, 17th-century England reminds us that despite the enormous leaps we've made in science and technology, humans themselves remain in many ways the same: imperfect, not always rational and still deeply vulnerable to novel nasty microbes. Read more: |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "plague" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment