Pulmonary Immune Dysregulation and Viral Persistence During HIV Infection

“Bubonic Plague Strikes In Mongolia: Why Is It Still A Threat? - NPR” plus 3 more |

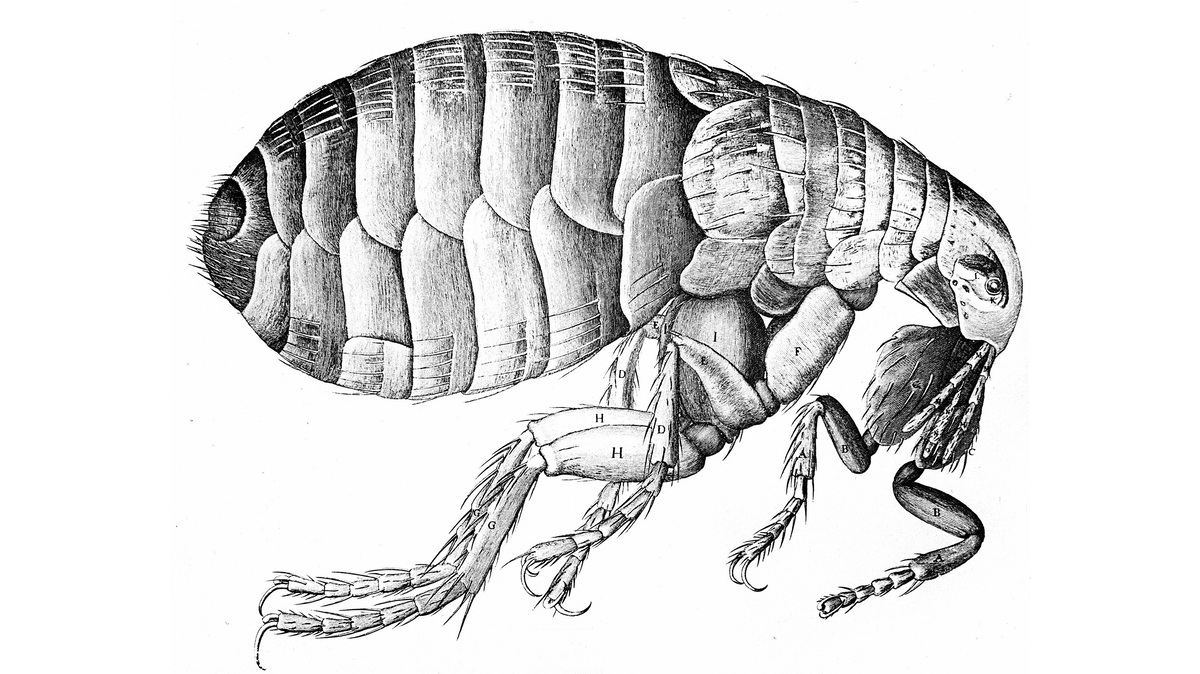

| Bubonic Plague Strikes In Mongolia: Why Is It Still A Threat? - NPR Posted: 07 May 2019 06:50 PM PDT  The bacterium that causes the plague travels around on fleas. This flea illustration is from Robert Hooke's Micrographia, published in London in 1665. Getty Images hide caption  The bacterium that causes the plague travels around on fleas. This flea illustration is from Robert Hooke's Micrographia, published in London in 1665. Getty ImagesThe medieval plague known as the Black Death is making headlines this month. In Mongolia, a couple died of bubonic plague on May 1 after reportedly hunting marmots, large rodents that can harbor the bacterium that causes the disease, and eating the animal's raw meat and kidneys – which some Mongolians believe is good for their health. This is the same illness that killed an estimated 50 million people across three continents in the 1300s. Nowadays, the plague still crops up from time to time, although antibiotics will treat it if taken soon after exposure or the appearance of symptoms. Left untreated, the plague causes fever, vomiting, bleeding and open, infected sores — and can kill a person within a few days. The ethnic Kazakh couple died in Bayan-Ulgii, Mongolia's westernmost province bordering Russia and China. It is not clear what treatment they received, if any. The incident prompted local panic. The government ordered a quarantine for six days for the region, preventing scores of tourists from leaving the area. At least one aircraft was examined by health officials in contamination suits. After no new cases appeared by Monday, the quarantine was lifted. Every year, according to the U.S. National Center for Zoonotic Disease, at least one person in Mongolia dies from the plague, usually after coming into contact with marmots. But they probably don't contract the disease from eating the animal's flesh, says David Markman, a researcher at Colorado State University. A person's stomach typically kills a lot of harmful bacteria before the germs are able to cause an infection, Markman says. Yersinia pestis, the bacterium causing the plague, lives in infected animals, particularly rodents, and is usually spread by fleas. "The vast majority of human cases are a result of contracting it from a flea bite," Markman says — just as mosquitoes transmit malaria from person to person. A Plague Primer The plague swept Europe 700 years ago, killing a third of the population. It was called the Black Death, possibly for dark patches caused by bleeding under the skin. It killed millions in China and Hong Kong in the late 1800s before scientists began associating the illness with rats and eliminating rodent populations. The plague comes in three forms. If a person gets bitten by an infected flea, they'd most likely develop bubonic plague, named for the painful lumps, or "buboes," where the bacteria multiply. The bacteria can also get into the bloodstream, causing septicemic (or blood poisoning) plague, and can also spread to the lungs, causing pneumonic plague. The World Health Organization considers this variant to be one of the deadliest infectious diseases because it is highly contagious – spread by coughing — and the fatality rate is 100 percent if untreated. Early symptoms of the plague can mimic the flu — including lethargy and swelling or stiffness in joints and lymph nodes. If someone begins exhibiting these symptoms after coming into contact with rodents or with pets in regions where the plague exists among animal populations, they should seek medical care immediately, Markman says. Transmission Techniques The bacterium that causes the plague will hook onto the lining of a flea's gut and stomach, growing into a film that can clog the insect's digestive passage. The next time the flea goes for a blood meal, it pukes into whatever animal it's feeding on (usually a rodent), spreading the bacteria. Once a rodent is infected, the illness can spread to other wild animals as well as cats, dogs and people within flea-jump range. "What we see in the West is the fleas will crawl up to the entrance of the burrow and wait for a host to come by," says Ken Gage, who studies vector-borne diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "If they get on another rodent that they can live on, then they've been successful. But they can also jump on humans or on dogs or coyotes or cats." Sometimes, that new host can transport the fleas a few miles away and spread them to other animals. Cats, which are highly susceptible to the disease, can also pass the infection to humans directly by coughing, biting and clawing. The 21st Century Outlook In modern times, the plague periodically pops up across the globe — though at minor levels compared to its heyday. Between 2010 and 2015, there were more than 3,000 cases reported, with 584 deaths. The bacterium thrives in dry, temperate areas like the American Southwest and in North and East Africa, South and Central Asia and parts of South America. The U.S. tends to see between one and 17 human cases a year. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the disease likely hitched a ride to the U.S. in 1900 on flea-infested rats, which had boarded steamships in Asia. Since then, infected fleas have taken up residence on rodents including chipmunks, squirrels and prairie dogs across the southwest. Between 2015 and 2017 in New Mexico, there were 11 cases of the plague in humans, including one death. Paul Ettestad, a public health veterinarian for the New Mexico state health department, says prairie dogs are particularly vulnerable to plague. If a whole colony gets the illness, the bacteria amplify. "It's like putting a match to a grass prairie," he says. "Whoosh." In places with poor access to health care, the illness can be deadly on a larger scale. That's what happened in Madagascar. The country sees between 280 and 600 infections annually. But in August 2017, health authorities began seeing an uptick in cases — particularly in pneumonic plague. After more than 200 deaths, the outbreak was contained by late November 2017. Medical teams confirmed suspected cases, treated patients quickly, advised the use of face masks to prevent infection and monitored international travel. But it's hard to declare a permanent end to an outbreak. The plague can persist in rodent populations, especially wild ones, for decades without affecting humans – and then can re-emerge. Markman's research indicates that the plague bacterium can survive and multiply in microbes in soil and water. Markman hypothesizes that when ground-dwelling rodents, like marmots and prairie dogs, dig in the soil, they may encounter the bacterium, then spread it through fleas. But he cautions that more research needs to be done, saying there are likely many reasons why the plague is still around in 2019. Melody Schreiber (@m_scribe on Twitter) is a freelance journalist in Washington, D.C. |

| Bubonic Plague Kills Couple, Quarantines Tourist Flight And Causes Border Chaos - Forbes Posted: 03 May 2019 05:55 AM PDT  According to a report in the Siberian Times on Friday, "the Mongolian authorities have confirmed the deaths of a husband and wife in the country's western Ulgii district," a spokesperson for the district's emergency management said that "preliminary test results show that bubonic plague likely caused the deaths of the two people." Pictures published by the newspaper showed emergency responders in hazmat clothing checking a tourist plane that had flown into the country's capital from the affected area. The newspaper also reported that "an 'indefinite quarantine' period has been declared to prevent the plague from spreading." It was unclear which people or locations would be impacted by those quarantine restrictions. There were almost 160 people on the tourist flight out of the affected area, those who originated in the immediate vicinity of the infection were taken to hospital, while the rest were examined near the airport under supervision. "A team from the National Centre for Communicable Diseases and Specialised Border Inspection carried out the onboard checks." Other reports claimed that the border between Mongolia and Russia was closed quickly and unexpectedly, hitting Russian tourists from Siberia and the Urals. The Moscow Times reported that the Mongolian "authorities placed its border with Russia under 'indefinite quarantine', leaving Russian tourists stranded... at least nine tourists sought help from the Russian consulate, while a border officer in Russia's frontier republic of Altai said the border closures were due to the extended May holidays." The border could be shut until Sunday 5 May. The couple, a 38-year-old man and his 37-year-old wife, reportedly fell ill after eating contaminated marmot. The consumption of Marmots, a particularly large variety of squirrel, is prohibited in Mongolia and clearly for good reason. According to the Siberian Times, the man died on 27 April and his wife three days later. They leave four children. The bubonic plague is caused by Yersinia pestis, a bacterium found in (generally small) mammals - like rats, judging the history books. Europe's Black Death killed more than 30% of the continent's population in the 14th century. The plague, which can now be treated, can kill inside a day albeit it usually takes longer. The disease is treatable with antibiotics but hundreds have died around the world in recent years. Prevention relies on not touching (or obviously eating) dead animals in those areas where the plague is present. Without treatment, the plague kills up to 90% of those infected within ten days. With treatment, the percentage of fatalities reduces to around 10%. The WHO reports that of the 3,248 cases recorded between 2010 to 2015, there were 584 deaths. In 2014, 30,000 people were confined to their neighborhoods or quarantined when a man died from the bubonic plague in the Chinese city of Yumen, in a particularly extreme response. Again, contact with a contaminated marmot was blamed for the infection. According to the Guardian, the Chinese authorities "consider plague to be one of two Class 1 infectious diseases, along with cholera. When a person falls ill under their jurisdiction, they are entitled to label certain zones 'infection areas' and seal them off." In the U.S., the response is somewhat more measured. Last year, a child in Idaho was treated for the disease. A health department spokesperson said at the time that "it is not known whether the child was exposed to plague in Idaho or during a recent trip to Oregon. The plague has historically been found in wildlife in both states. Since 1990, eight human cases were confirmed in Oregon and two were confirmed in Idaho." No further deaths or infections have been reported at the time of writing in Mongolia, but given the nature of the plague that could change. In the meantime, wherever you are, marmots are clearly best avoided. |

| Posted: 05 May 2019 02:03 PM PDT  Wong Chut King lived in squalid conditions in the cellar of San Francisco's Globe Hotel. It was a rat-infested space in the city's Chinatown that he shared with as many as three roommates all taking turns sleeping on the same bed. When a painful lump appeared on Wong's groin, the 41-year-old laborer, fearing he'd contracted a venereal disease, consulted a local Chinese doctor. The doctor prescribed an herbal remedy, yet Wong's temperature continued to soar. He also became nauseous, diarrheic and delusional. Before Wong could be overtaken by the disease, the men sharing his cramped living quarters carried him to a nearby... |

| Wait, You Can Still Get the Plague? - Slate Posted: 08 May 2019 02:48 PM PDT A potential agent of plague! Barbara Sax/AFP/Getty Images The plague has, at various points in history, been responsible for wiping out over half of the human beings in Europe, killing some 10,000 people a day in what is now Istanbul, and possibly even felling the Roman Empire. At the beginning of this month, the plague again reared its head and killed a couple in Mongolia. The Washington Post's two-beat headline sums it up superlatively well: "A couple ate raw marmot believed to have health benefits. Then, they died of the plague." While it makes sense, cosmically, that the plague would be yet another thing happening in the year of 2019 , the plague never actually went anywhere. We just have modern health precautions for avoiding it now, as we do for many illnesses that are just a couple bites of undercooked meat away from killing us. Each year in the U.S., an average of seven people still get the plague. The most common is bubonic, though they're all caused by the same bacteria. But it's "really a wildlife disease," biologist Nils Christian Stenseth told Pacific Standard earlier this year. It's caused by bacteria that likes to live in rodents, though within the past year, three cats in Wyoming have been diagnosed with the plague, too. Flea bites are the main way it spreads to humans, according to a fact sheet from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. You can also get it from touching, skinning, being coughed on—or presumably, wholesale ingesting—an animal with the plague. "Especially sick cats," notes the fact sheet, which means the Wyoming cat owners ought to be careful. Dogs can get the plague too, which is why the CDC further advises that you don't let them sleep in your bed in plague-y areas of the U.S. What are those areas? Mostly Western states. Plague arrived here at the beginning of the 20th century via rats hitching rides on ships from Asia, where it spread to rodents in states including California and New Mexico (a location in which I have recently snuggled my dog!). The prairie dog can also get the plague, in fact, it is the CDC fact sheet's poster-animal for the infection. The Badlands National Park in South Dakota where plague was detected in the animals in 2009, is outfitted with dramatic signs that warn "PRAIRIE DOGS HAVE PLAGUE!" Visitors are advised not to get too close to the cuddly critters. This all sounds scary, understandably, as it's the PLAGUE. But while outbreaks still occur—one killed 209 people in Madagascar in 2017—if you're in the U.S., you're probably just fine. We can thank modern protections like bug spray, flea treatment, and latex gloves for keeping us separated from the bacteria that transmit it. The last urban epidemic in the U.S. was in 1925 in LA, according to the CDC. There's also a plague vaccine, but the disease is so rare that it's not even available in the States. And even if you do get the plague, you probably will not die from it: from 2000-2017, it killed a grand total of…12 people in the U.S. That low number is thanks to antibiotics. Just the same, stay away from the prairie dogs, and cook your marmots thoroughly. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "what year was the plague" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment